76. TO THE BONE

I

recently saw a video posted to Facebook that showed the workings of a humongous

Chinese poultry processing plant, where thousands of workers stand in place chopping,

gutting, and packaging a never-ending supply of chickens moving relentlessly

along on conveyer belts. Dressed in hazmat-like, white protective clothing,

with masks allowing only their vacant eyes to show, they stare soullessly as they

do their robot-like tasks. It’s impossible to imagine what such dehumanizing

work does to a human being, but a glimpse of it is present in Lisa Ramirez’s promising

new play, TO THE BONE, at the Cherry Lane Theatre. The play is being offered as

part of this year’s Theatre: Village festival, titled E Pluribus, in which four

plays “celebrating America’s diversity” are being presented by the Axis

Theatre, the Cherry Lane, the New Ohio Theatre, and the Rattlestick Playwrights

Theater, all prominent West Village venues.

|

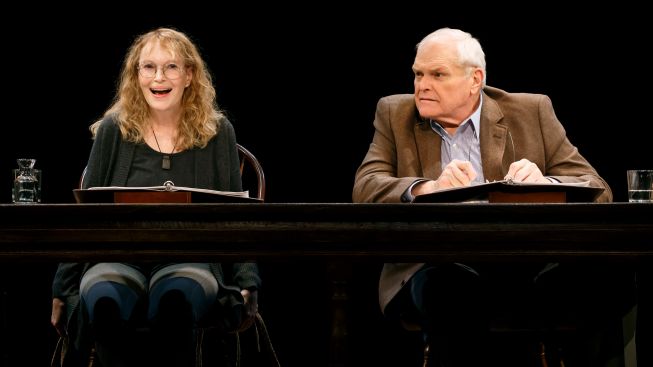

| From left: Lisa Fernandez, Annie Henk, Lisa Martinez. Photo: TO THE BONE company. |

Miss Ramirez, who also offers a

persuasive performance as Olga, one of three Hispanic poultry processors, shines

a light on the dilemma of undocumented immigrant female workers in much the

same way that Elizabeth Irwin does for Mexican busboys in her recent MY MAÑANA

COMES, where the fear of being discovered and deported never ends. Much of the dramatist’s inspiration comes from interviews she conducted with undocumented Latino workers. Ms. Martinez’s

two-act play, which runs a slightly longish two hours, is less consistent and

polished than Ms. Irwin’s, but nevertheless provides a strong evening of

theatre, especially in this vividly directed (by Lisa Peterson) and expertly

performed production.

To establish Olga’s house, the poultry plant, and

other nearby places, designer Rachel Hauck has totally reconfigured the small

theatre at the rear of the Cherry Lane’s lobby from the conventional end stage

arrangement it normally uses. Two rows of seats facing the entrance doors surround

a three-quarters round acting area. There’s a small kitchen at extreme audience

left, in the space between one bank of seats and the other, and a windowed room

at the upstage end of the left seating bank. Up a small flight on the upstage

wall at audience right are the windowed living quarters of Olga’s coworkers, Reina

and Juana, with the bedroom of Lupe, Olga’s daughter, below. A movable doorway

stands in its frame at center and factory lockers are placed in a corner at

audience right. Lining the walls are stacked chicken crates, each with a flickering

light inside to suggest a living presence. Serving multiple purposes, such as for furniture, car seats, and

assembly line platforms, are four more crates. Although the minimalist effect

is generally satisfactory, the layout of the characters’ living arrangements is

rather vague and confusing.

In act one we watch the daily routines of Olga,

Reina (Annie Henk), and Juana (Liza Fernandez) as they get up, do their morning

washing and eating rituals, get driven to their Sullivan County factory by the

Guatamalan cabby Jorge (Dan Domingues), and perform their drearily repetitious jobs.

They are ragged over the loudspeaker by their cruelly demanding American boss,

Daryl (Haynes Thigpen), and drilled to work faster by their Honduran floor

supervisor, Lalo (Gerardo Rodrigues). Lalo is outwardly ruthless, but inwardly

sympathetic, as his own well-being depends on his satisfying Daryl’s demands.

Daryl himself is pressured by orders from “corporate” to provide more product.

Of the three women, Olga, a Salvadoran, is the only one with a green card, while Reina and

Juana are illegals. Olga’s 20-year-old daughter, Lupe (Paola Lázaro-Muñoz), works

at a medical clinic and aspires to attend NYU’s law school. The only plant worker who dares to

oppose the management over issues like work breaks and the like is the feisty Olga,

whose green card gives her a sense of security impossible for the others, one

of whom, Juana, suffers both from physical weakness at work and from psychological issues

that cause her to sleepwalk like a ghost. Before act one ends, we also meet Carmen

(Xochitl Romero), Reina’s young Honduran niece, who has slipped across

the border to find work at the poultry plant. Sad and vulnerable, with a taste

for poetry, she needs money for a parent’s operation.

Act two moves away

from its emphasis on the debilitating effect of work conditions to

the story of Carmen, with whom Jorge soon falls in love. The plot becomes increasingly

melodramatic, with rape and retribution taking prominence. Olga’s fury has no

bounds and helps to inspire events that lead to violence and tragedy. Gone are

the choreographically precise rituals smartly choreographed by Ms. Peterson,

replaced by a more insistently naturalistic performance mode. Although the rape

is intrinsic to the exploitative environment, it seems too clichéd a

device, and muddles the socio-political through line, especially with the

rapist being depicted as a monster of unregenerate evil.

Ms. Ramirez’s spicy

language, much of which I believe is intended to be understood as spoken in

Spanish (albeit with only hints of Hispanic accents), carries the action

forward with dynamic force, and is rendered with the kind of conviction

I found so lacking the other evening in SCENES FROM A MARRIAGE. Ms. Ramirez

acts Olga with fiery anger and determination, making her sympathetic despite her

destructively irate temperament. Ms. Lázaro-Muñoz brings memorable

intelligence, humor, and emotional variety to the chubby, skateboard-riding,

hip-hop reciting Lupe, while Ms. Romero plays Carmen with heartbreaking

sweetness and sorrow. So believable is her air of victimization that I was amazed

to read in her bio that Glamour Magazine chose

her as one of the “Top 10 Funniest Food Bloggers.” Ms. Henk is completely

credible as the determined Reina, and Ms. Fernandez is suitably sensitive as

Juana, although her long, almost whispered monologue to Juana is barely

audible. Both Mr. Domingues and Mr. Rodriguez do excellently by their roles,

and Mr. Thigpen, forced to be a two-dimensional villain, makes Daryl someone

you want to hiss.

Jill BC Du Boff has

outdone herself with an extraordinary sound design combining perfectly chosen

musical selections and auditory effects (including what one would hear in a poultry processing plant), while Russell H. Champa’s lighting does

wonders to create the right emotional atmosphere in the tiny space. Theresa

Squire’s costumes add authenticity to this bedraggled corner of existence.

TO THE BONE

is part slice of life, part expressionism, and part melodrama. You may not like

every part but what remains should be finger lickin’ good.

.jpg)

.jpg)