|

| Showgirls in "Loveland" number. |

FOLLIES [Musical/Marriage/Period/Show

Business] B: James Goldman; M/LY: Stephen Sondheim; D: Harold Prince, Michael

Bennett; CH: Michael Bennett; S: Boris Aronson; C: Florence Klotz; L: Tharon

Musser; P: Harold Prince i/a/w Ruth Mitchell; T: Winter Garden Theatre;

4/4/71-7/1/72 (521)

|

| Sheila Smith, Ethel Barrymore Colt, Alexis Smith, Dorothy Collins, Helen Blount, Yvonne DeCarlo. |

Put

together by the leading musical theatre production team of the decade, Follies—now a modern classic—was widely considered

a revolutionary step forward for a Broadway musical. Despite a numerically healthy

run, it nonetheless lost its $800,000 investment, made even worse by the failure

of its projected road tour to be realized.

Set within the crumbling walls of a

soon-to-be-torn-down Broadway theatre, the story brings together a group of

old-time Follies showgirls and their

husbands for a nostalgic reunion prior to the swinging of the wrecker’s ball. The reference is to the old-time Ziegfeld Follies extravaganzas but the impresario here is named Dmitri Weissmann (Arnold Moss).

The

intermissionless show uses a Proustian device of mingling past and present

times so that the showgirls are viewed as they are and as they were, their

younger selves portrayed, ghost-like, in black and white, by younger actresses.

The main action deals with the marital difficulties two couples—Sally and

Buddy Plummer (Dorothy Collins and Gene Nelson) and Phyllis and Ben Stone

(Alexis Smith and John McMartin)—have been facing, their hopes that the reunion

with old loves (Sally had once loved Ben) and memories will somehow give their

unhappy lives a new direction, and their final determination to go on staunchly

facing life with their partners. Marti Rolph and Harvey Evans played

the younger Sally and Buddy, while Young Phyllis and Young Ben were handled by

Virginia Sandifur and Kurt Peterson.

|

| Kurt Peterson, Virginia Sandifur, Harvey Evans, Marti Rolph. |

To Henry

Hewes the result was not a simple nostalgic look backwards, but a presentation

of “the ghosts of our past as painful exhumations.” The show received wildly

varying reviews, some finding it brilliant and moving, others sentimental and

trite. The main target of criticism was the book, but even the negative reviews

tended to laud the music, lyrics, set, and costumes. Few failed to be impressed

by the concept, its imaginative execution, and the excellent cast of

middle-ages female stars whose waning beauty added a special melancholy to the

event.

|

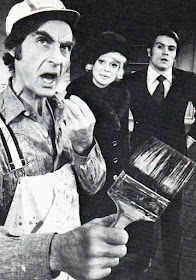

| Ursula Maschmeyer, Justine Johnston, John Grigas. |

Alexis

Smith was singled out for her radiant performance in a large company that

included Graciela Daniele, Fifi D’Orsay, Yvonne De Carlo, Ethel Shutta (once

actually a Ziegfeld girl), Justine Johnston, Ethel Barrymore Colt, and Mary

McCarty. Stephen Sondheim’s score was seen as a marvelous pastiche of old-time

Broadway styles. Among its most memorable numbers, which have grown richer with

the years, are “I’m Still Here,” “Could I Leave You,” and “Losing My Mind.” Jack

Kroll thought Sondheim’s creations “transcend the pitfalls to burst out in a

cornucopia of tunes and lyrics that give stinging detail, with and poignance to

all of the theme’s implications.”

|

| Gene Nelson. |

Walter

Kerr was the principal objector, finding Follies

“tedious,” evincing “ingenuity without inspiration,” and having a “trivial”

libretto. Since the New York Times’s

other reviewer at the time, Clive Barnes, also had reservations, Martin

Gottfried published in that paper a spirited defense in which he declared Follies a “standard” for the American

musical theatre to emulate: “Follies is

a concept musical, a show whose

music, lyrics, dance, stage movement, and dialogue are woven through each other

in the creation of a tapestry-like theme (rather than in support of a plot).”

|

| John McMartin (top hat and tails) and company |

The show

was buried in awards and nominations, winning Best Musical recognition from the

New York Drama Critics Circle, Outstanding Production from the Outer Critics

Circle, a Best Book Tony nomination for Goldman, a Best Score Tony win for

Sondheim, a Drama Desk Award for Stephen Sondheim’s lyrics, a Tony nomination

for Best Supporting Actor, musical, for Gene Nelson, a Tony win for Alexis Smith

as Best Actress, Musical, a shared Drama Desk Award and Tony for Hal Prince and

Michael Bennett for direction, a Tony for Bennett’s choreography, a Tony and a

Drama Desk Award for Boris Aronson’s scenic designs, a Drama Desk Award for

Florence Klotz’s costumes, and a slew of Variety Poll selections, among others.

Follies has received multiple revivals,

regionally, internationally, and on Broadway, the principal examples of the

latter being in 2001 and 2011.