|

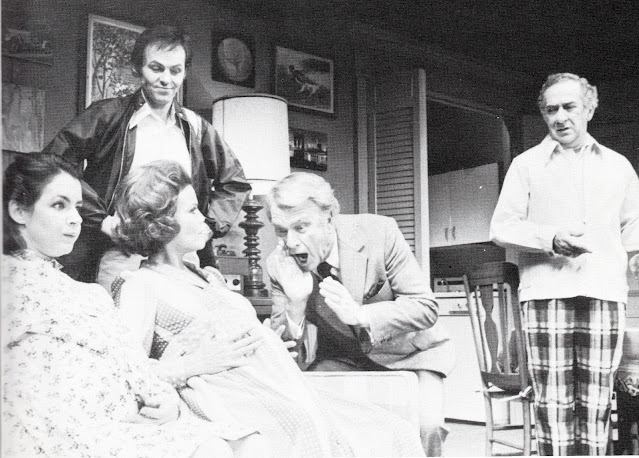

| Roderick Cook, Jamie Ross, Barbara Cason. |

OH COWARD! [Musical Revue] M/LY: Noël Coward; D: Roderick Cook;

S: Helen Pond and Herbert Senn; P: Wroderick Productions, Inc.; T: New Theatre

(OB): 10/4/72-6/17/73 (294)

English playwright-actor Roderick

Cook, a Noël Coward specialist, devised, directed, and performed in this

sparklingly tasteful, intelligent, and deceptively simple Off-Broadway revue of

the master’s songs and jottings. Cook had originated it for the Vancouver

International Festival in 1968, titled And Now Noël Coward . . . An

Agreeable Impertinence, and starring Dorothy Loudon. After negative critical

response, it was reworked for Broadway and called Noël Coward’s Sweet

Potato, opening on September 29, 1968, and garnering 44 performances. Cook revised it again as Oh Coward!, produced in in Toronto and elsewhere, and then brought it to Off

Broadway in this production.

With a modest accompaniment from

twin pianos and a drum, the two-man (Cook and Jamie Ross), one woman (Barbara

Cason), formally-garbed cast provided a spot-on interpretation of Coward’s

stylish sophistication and verbal marksmanship, with every chiseled word

precisely spoken, and every tuneful note sung with clarity and charm. Even the

curtain, showing a double-headed caricature of Coward, one face a bit sour, the

other slightly smiling, contributed to the overall effect.

So aptly was it done that the lack

any particularly noteworthy voice—Mel Gussow thought Ross the best singer—was

of secondary concern. The spoken passages were plucked from Coward’s plays and

books, most of the songs from his shows. A few songs—like Cole Porter’s “Let’s

Do It”—had been sung by Coward although someone else wrote them.

Among the many musical numbers—created

over 38 years—were “Something to Do with Spring,” “Ziegeuner,” “We Were

Dancing,” “Sail Away,” “Room with a View,” “If Love Were All,” “Mrs.

Worthington,” “Mad Dogs and Englishmen,” “Gertie,” “Mad about the Boy,”

“Someday I’ll Find You,” and “I’ll See You Again.”

Oh Coward! was

played straight. Gussow reported, “Wisely, Mr. Cook and his companions play

everything tight to the chest. They barely crack a smile, even when laughing—but

we laugh. Nothing is spoofed or ridiculed. There is no overstatement or

overproduction. . . . ‘Oh Coward’ lets Sir Noel speak for himself.” John Simon

referred to the approach as a perfect example of “high camp,” meaning

“subversive or even anarchic views given the most genteel and soigné

expression.” He thought the revue “a small diamond, but . . . a very nearly

flawless one.” Like several others, he made special note of the originality of Cook’s interpretation of the song, “The Party’s Over Now,” from Words and Music, long associated with

Beatrice Lillie’s eccentric rendition. Here, though, it was proffered as the

unhappy remembrance of a man suffering the aftereffects of a “marvelous party”

that was anything but “marvelous.”

Oh Coward! subsequently played in

London, and, in 1986, was revived at Broadway's Helen Hayes Theatre for 56 performances,

earning Tony nominations for Cook and Catherine Cox.