91. ON THE

TOWN

|

| 1944 Playbill for ON THE TOWN. |

|

| 1971 Playbill for ON THE TOWN. |

|

| 1998 Playbill for ON THE TOWN. |

|

| 2014 Playbill for ON THE TOWN. |

|

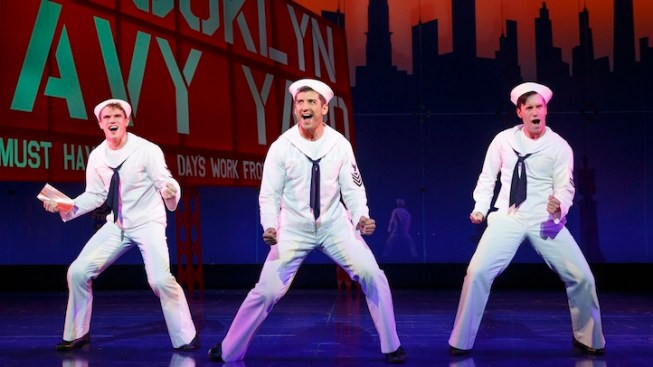

| From left: Jay Armstrong Johnson, Tony Yazbeck, Clyde Alves. Photo: Joan Marcus. |

The divine Megan Fairchild plays Ivy Smith, the Miss

Turnstiles Gabey longs for; Ms. Fairchild’s background as principal dancer with

the New York City Ballet has prepared her for the show’s many dancing chores,

which she performs with superlative beauty and grace (especially that stunning

dream ballet), while Alysha Umphress as the burlesque-tinged, plumply pulchritudinous, erotically supercharged, brassily engaging taxi driver, Hildy, who

hooks up with Chip, offers a hilarious counterpart to Ms. Fairchild’s ethereal loveliness.

As Claire De Loon, the anthropologist who finds romance with Ozzie in the

shadow of a Museum of Natural History dinosaur (which also gets to dance!),

Elizabeth Stanley, makes her every moment on stage both sexy and sensational.

Jackie Hoffman, in several roles, but especially as the alcoholic singing

teacher Maude P. Dilly, exudes laugh-out-loud comedy from every gin-soaked pore. Allison

Guinn as Hildy’s homely friend, Lucy Schmeeler, and Michael Rupert as Claire’s

distinguished boyfriend, Pitkin, a gray-haired judge who “understands”

everything (until he doesn’t), are equally seamless in their comic turns.

John Rando’s flawlessly rambunctious, consistently energetic,

and dazzlingly inventive direction, supplemented by the remarkably fresh and

creative choreography of Joshua Bergasse (who succeeds in matching, if not outdoing, the original

choreography of Jerome Robbins), make this revival into something unexpectedly

rich and vibrant. There are dozens of thrilling moments to relish but, if I were

threatened with being run down by a speeding cab, I guess I’d choose “Come Up

to My Place,” imagined as a wild taxi ride through the canyons of New York,

captured in Beowulf Borritt’s brilliant projections, as Hildy steers crazily and

Chip flies every which way, courtesy of a trick car seat that deserves an

award for doing what you might have thought possible only in an animated movie.

The original orchestration, best known for only a single song, “New York, New York,” (the Bronx

is up, and the Battery’s down), played by a 28-piece orchestra with musical direction

by James Moore (who also conducts), has never sounded better. Mr. Borritt’s gorgeously

evocative sets and projections, the miraculous lighting of Jason Lyons, the

vivid period costumes of Jess Goldstein, and the impressive contributions of so

many others, make it imperative that you see this terrific revival. Did I like

it? All of my ten thumbs are up!

Now for a little history. The 1944-1945 season already had a memorable parade of hits—including SONG OF NORWAY, ANNA LUCASTA, BLOOMER GIRL, I REMEMBER MAMA, HARVEY, THE LATE GEORGE APLEY, and DEAR RUTH—when ON THE TOWN arrived on December 28. It was the first Broadway show for the team of composer Bernstein and librettist-lyricists Adolph Green and Betty Comden, each of whom would become musical theatre icons. Their contributions here included such songs as the above-mentioned “New York, New York” and “Come Up to My Place,” as well as “Carried Away,” “Lonely Town,” “I Can Cook, Too,” “Lucky to Be Me,” and “Some Other Time.” Comden and Green also proved their worth as performers, with the attractive Comden playing Claire de Loon and Green essaying Ozzie, whose dancing was limited (as in the 1949, film, where Jules Munshin played Ozzie, Frank Sinatra was Chip, and Gene Kelly was Gabey). The pair joined the show at Bernstein’s urging to replace the original lyricist, John Latouche.

|

| Megan Fairchild. Photo: Joan Marcus. |

|

| From left: Jay Armstrong Johnson, Alysha Umphress, Tony Yazbeck, Elizabeth Stanley, Clyde Alves. Photo: Joan Marcus. |

Now for a little history. The 1944-1945 season already had a memorable parade of hits—including SONG OF NORWAY, ANNA LUCASTA, BLOOMER GIRL, I REMEMBER MAMA, HARVEY, THE LATE GEORGE APLEY, and DEAR RUTH—when ON THE TOWN arrived on December 28. It was the first Broadway show for the team of composer Bernstein and librettist-lyricists Adolph Green and Betty Comden, each of whom would become musical theatre icons. Their contributions here included such songs as the above-mentioned “New York, New York” and “Come Up to My Place,” as well as “Carried Away,” “Lonely Town,” “I Can Cook, Too,” “Lucky to Be Me,” and “Some Other Time.” Comden and Green also proved their worth as performers, with the attractive Comden playing Claire de Loon and Green essaying Ozzie, whose dancing was limited (as in the 1949, film, where Jules Munshin played Ozzie, Frank Sinatra was Chip, and Gene Kelly was Gabey). The pair joined the show at Bernstein’s urging to replace the original lyricist, John Latouche.

|

| Jay Armstrong Johnson, Alysha Umphress. Photo: Joan Marcus. |

During the time the show was being written,

Bernstein and Green needed operations, the former for a deviated septum, the

latter for tonsillitis, so they saved time by going into the same hospital at

the same time so they could collaborate in their room while

recuperating. Wrote Joan Peyser in her biography, Bernstein: “It was quite a scene in that hospital room—rather like

a Marx Brothers movie. Radios blared. Arguments accelerated over card games.

Pieces of ON THE TOWN were sung full voice. But they did a lot of work.” Comden

and Green were initially opposed to the show’s title and to its three-sailor

theme, thinking the result would be too close to a grade-B movie.

Although ostensibly based on “Fancy Free,” a

well-received 1944 ballet choreographed by Jerome Robbins and composed by Bernstein

about three gobs on leave and trying to pick up girls in New York, the show

used none of Bernstein’s melodies or Robbins’s dances from that piece, and the

composer insisted that the two works were quite different, only the three

sailors concept tying them together. The original cast had John Battles as

Gabey (replacing the still unknown Kirk Douglas, of all people, because Douglas

couldn’t sing—nor dance, it might be added) and Chip was Cris Alexander (better

known as a celebrity photographer). Battles’s other major Broadway musical role

was in ALLEGRO, which will soon open in a revival at the CSC, so perhaps

someone should commemorate his contributions (he died in 2009).

The book was generally dismissed as insignificant but few denied its cleverness and effectiveness within the framework of the show’s premise. Much pleasure was gained from its frequent satiric sallies at aspects of New York life and culture. Lewis Nichols in the New York Times celebrated the show’s arrival by noting: “Everything about it is right. It is fast and is gay, it takes neither itself nor the world too seriously, it has wit. Its dances are well paced, its players are a pleasure to see, and its music and backgrounds are both fitting and excellent.” Much the same could be said of the current revival. John Mason Brown in the Saturday Review reveled in what he regarded as a masterpiece of innovation, a show that was to the urban landscape what OKLAHOMA! was to the rural.

As originally written, the script called for the scenes to be tied together by a prologue in night court, a locale to which the action would periodically return. The writers loved the concept but director Abbott hated it, and early on told them that the prologue and flashbacks would have to go. Green was enraged and he and Comden fought with Abbott to retain the material, to which he responded, says Peyser, with: “OK. I’ll tell you what. You can have either me or the prologue.” Abbott stayed, the prologue, etc., went, along with other cuts before the script was finished.

Especially noteworthy was how effectively Robbins had brought the art of ballet to Broadway dance (this was his Broadway debut as a musical comedy choreographer). His dances, said Rosamond Gilder of Theatre Arts, proved him “adept in the art of translating ordinary, insignificant events and gestures into the poetic idiom of the dance.” One of his most distinctive creations, Gilder declared, was the subway scene, with the movement of the throng of workers and gum-chewing secretaries gradually blending into dance. “The rhythm of the moving train, picked up by the music, is accentuated little by little in one swaying figure, then another, and finally bursts into a pattern of movement that embraces the whole stage, bursting the confines of realism and becoming an expression of all the weariness, hurry and passion for escape with which every clattering subway train is laden.” Robbins, quoted in Otis L. Guernsey’s Broadway Song and Dance, later commented: “One of the important things in the show that was not noted was the mixed chorus. It was predominantly white, but there were four black dancers—and, for the first time, they danced with the whites, not separately, in social dancing. We had some trouble with that in some of the cities we went to.” There are only two black dancers (Julius Carter and Tanya Birl) in the current revival, although there’s an Asian American dancer, Christopher Vo, and the black singer-actor Phillip Boykin makes a powerful impression in several supporting roles.

Bernstein’s music was not universally approved, but most critics would have agreed with E.C. Sherburne of the Christian Science Monitor: “The varieties of his rhythms, his satirical tonal embroideries, and the surprises offered by his vaulting rhythms leave the listener startled with the realization that he made it, like the man on the flying trapeze.”

Every principal actor came in for accolades, but most highly acclaimed was dancer Sono Osato as Miss Turnstiles. “She manages,” wrote John Mason Brown, “to combine the cool beauty of Sorine’s ‘Pavlova’ with a sense of humor subtler than Fannie Brice’s, but Brice-like in its contagious qualities. Miss Osato is a young person, arresting and brilliantly endowed, who is already a personage.” Despite being the daughter of a Japanese man and a woman of French-Irish-Canadian descent, she was cast in a Caucasian role, this being a daring example of early nontraditional casting, especially since it was right in the midst of this country’s war with Japan and while her father was in an internment camp. Ms. Osato, by the way, is still alive at 95, and one wonders if anyone will make the effort to bring her to the show, provided she’s able and interested. What a publicity coup that would be!

My theatre companion at the revival was my dear friend, Mimi Turque Marre, who in 1945 was a little girl from Brooklyn named Mimi Strongin playing the child’s role of Bessie in the original production of CAROUSEL, at the Majestic Theatre on W. 44th Street. CAROUSEL was produced when the original ON THE TOWN was still running at the Adelphi, ten blocks uptown; during its run ON THE TOWN migrated to the now gone 44th Street Theatre, just across from the Majestic, where it was that playhouse’s last production, before it moved on to the Martin Beck (now the Al Hirschfeld).

At the beginning of ON THE TOWN, a large 48-starred American flag is projected on a scrim and the audience stands to sing the national anthem. Mimi, a Broadway musical theatre veteran (FIDDLER ON THE ROOF, KISS OF THE SPIDERWOMAN, etc.), let fly with a still thrilling voice that had spectators turning to see where it was coming from. I felt privileged to be singing alongside this part of Broadway history, and to see that Mimi’s still a helluva gal and ON THE TOWN’s still a helluva show!

The book was generally dismissed as insignificant but few denied its cleverness and effectiveness within the framework of the show’s premise. Much pleasure was gained from its frequent satiric sallies at aspects of New York life and culture. Lewis Nichols in the New York Times celebrated the show’s arrival by noting: “Everything about it is right. It is fast and is gay, it takes neither itself nor the world too seriously, it has wit. Its dances are well paced, its players are a pleasure to see, and its music and backgrounds are both fitting and excellent.” Much the same could be said of the current revival. John Mason Brown in the Saturday Review reveled in what he regarded as a masterpiece of innovation, a show that was to the urban landscape what OKLAHOMA! was to the rural.

As originally written, the script called for the scenes to be tied together by a prologue in night court, a locale to which the action would periodically return. The writers loved the concept but director Abbott hated it, and early on told them that the prologue and flashbacks would have to go. Green was enraged and he and Comden fought with Abbott to retain the material, to which he responded, says Peyser, with: “OK. I’ll tell you what. You can have either me or the prologue.” Abbott stayed, the prologue, etc., went, along with other cuts before the script was finished.

Especially noteworthy was how effectively Robbins had brought the art of ballet to Broadway dance (this was his Broadway debut as a musical comedy choreographer). His dances, said Rosamond Gilder of Theatre Arts, proved him “adept in the art of translating ordinary, insignificant events and gestures into the poetic idiom of the dance.” One of his most distinctive creations, Gilder declared, was the subway scene, with the movement of the throng of workers and gum-chewing secretaries gradually blending into dance. “The rhythm of the moving train, picked up by the music, is accentuated little by little in one swaying figure, then another, and finally bursts into a pattern of movement that embraces the whole stage, bursting the confines of realism and becoming an expression of all the weariness, hurry and passion for escape with which every clattering subway train is laden.” Robbins, quoted in Otis L. Guernsey’s Broadway Song and Dance, later commented: “One of the important things in the show that was not noted was the mixed chorus. It was predominantly white, but there were four black dancers—and, for the first time, they danced with the whites, not separately, in social dancing. We had some trouble with that in some of the cities we went to.” There are only two black dancers (Julius Carter and Tanya Birl) in the current revival, although there’s an Asian American dancer, Christopher Vo, and the black singer-actor Phillip Boykin makes a powerful impression in several supporting roles.

Bernstein’s music was not universally approved, but most critics would have agreed with E.C. Sherburne of the Christian Science Monitor: “The varieties of his rhythms, his satirical tonal embroideries, and the surprises offered by his vaulting rhythms leave the listener startled with the realization that he made it, like the man on the flying trapeze.”

Every principal actor came in for accolades, but most highly acclaimed was dancer Sono Osato as Miss Turnstiles. “She manages,” wrote John Mason Brown, “to combine the cool beauty of Sorine’s ‘Pavlova’ with a sense of humor subtler than Fannie Brice’s, but Brice-like in its contagious qualities. Miss Osato is a young person, arresting and brilliantly endowed, who is already a personage.” Despite being the daughter of a Japanese man and a woman of French-Irish-Canadian descent, she was cast in a Caucasian role, this being a daring example of early nontraditional casting, especially since it was right in the midst of this country’s war with Japan and while her father was in an internment camp. Ms. Osato, by the way, is still alive at 95, and one wonders if anyone will make the effort to bring her to the show, provided she’s able and interested. What a publicity coup that would be!

My theatre companion at the revival was my dear friend, Mimi Turque Marre, who in 1945 was a little girl from Brooklyn named Mimi Strongin playing the child’s role of Bessie in the original production of CAROUSEL, at the Majestic Theatre on W. 44th Street. CAROUSEL was produced when the original ON THE TOWN was still running at the Adelphi, ten blocks uptown; during its run ON THE TOWN migrated to the now gone 44th Street Theatre, just across from the Majestic, where it was that playhouse’s last production, before it moved on to the Martin Beck (now the Al Hirschfeld).

At the beginning of ON THE TOWN, a large 48-starred American flag is projected on a scrim and the audience stands to sing the national anthem. Mimi, a Broadway musical theatre veteran (FIDDLER ON THE ROOF, KISS OF THE SPIDERWOMAN, etc.), let fly with a still thrilling voice that had spectators turning to see where it was coming from. I felt privileged to be singing alongside this part of Broadway history, and to see that Mimi’s still a helluva gal and ON THE TOWN’s still a helluva show!