“Seeing Red”

Most non-profit, subscription-based theatres—Off Broadway or on—can afford to allow their shows to continue until the end of their specified runs, critics be damned. While it’s always important—both financially and psychologically—to put as many fannies in the seats as possible, even poorly received shows can usually survive for their scheduled weeks with low audience turnout. That’s why a weak play like Gregg Pierce’s Cardinal, at the Second Stage’s Tony Kiser Theatre, is still playing; in a commercial venue, especially a Broadway one, its life would have been cut mercifully short.

Most non-profit, subscription-based theatres—Off Broadway or on—can afford to allow their shows to continue until the end of their specified runs, critics be damned. While it’s always important—both financially and psychologically—to put as many fannies in the seats as possible, even poorly received shows can usually survive for their scheduled weeks with low audience turnout. That’s why a weak play like Gregg Pierce’s Cardinal, at the Second Stage’s Tony Kiser Theatre, is still playing; in a commercial venue, especially a Broadway one, its life would have been cut mercifully short.

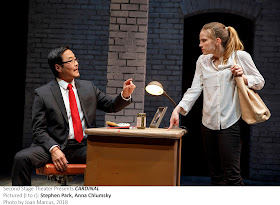

Pierce’s (Slowgirl) leaden, politically-tinged dramedy offers Anna Chlumsky a part not altogether different from her signature role as Amy Brookheimer on “Veep,” for which she’s received five Emmy nominations. In Cardinal she does what we already know she can do—comic bitchiness, eye-rolling frustration, ruthless ambition, and potty-in-the-mouth language. Without the support of the TV show’s snarky wit and driving comic edge, however, these qualities become annoyingly monotonous.

Instead of working in the upper echelons of D.C. politics, carrying on sexually and otherwise with various White House operatives, Chlumsky is now Lydia Lensky, a failed band manager turned amateur urban planner (she took a course). After living in Brooklyn, she’s returned to her hometown, the fictional Brindle, in upstate New York, to realize a project she’s concocted to revive the opioid-addicted, unemployment-afflicted burg.

Soon, Lydia’s in bed (literally and figuratively) with Jeff Torm (Adam Pally, “Happy Endings”), a geeky former high school acquaintance who’s now Brindle’s awkward, ineffectual mayor; he once had a love affair with Lydia’s sister, which acts like a faucet—on and off—in his relations with Lydia.

Lydia—still the brunt of ill will for a stupid high school prank she carried out that caused the town to suffer through a lengthy blackout—seeks to revitalize the place (declining since it lost its axle factory) by painting it cardinal red.

Jeff resists at first—he’d like to redevelop the waterfront instead—but soon accepts the notion; as Lydia explains while pitching it to the townspeople in a school’s “gymnatorium,” the red town will attract tourists, like the blue and yellow Moroccan and Mexican cities whose pictures she displays.

Pierce’s writing and the tone established by director Kate Whoriskey fail to clarify just how much we’re supposed to buy the possibility that Lydia’s dream might actually pay off. Moribund cities in upstate New York wouldn't be vacation bait if you painted them in every color of the rainbow. It's a crackpot idea that only makes the play, devoid of leavening laughter, that much more difficult to sit through.

Lydia’s ambitions become enmeshed with the aspirations of Li-Wee Chen (Stephen Park), a wealthy Chinese immigrant entrepreneur in New York’s Chinatown, who starts a tour bus operation for Chinese tourists in Brindle, creating a fictional backstory about local ghosts he thinks will draw visitors.

His handsome son, Jason (Eugene Young), however, whom he’d like to pair up with Lydia, is a romantic with little interest in his father’s operations. These seem little more than a clumsy attempt to satirize nativist fears of being overrun by hordes of racially different foreigners.

Opposing Lydia’s plan are Nancy (Becky Ann Baker, “Girls”) and Nat Prenchel (Alex Hurt), her autistic son, a talented pastry maker at their long-established bakery in the abandoned factory. The Prenchels resent Lydia’s I-know-what’s-best-for-you assertions and resist her determination to paint their shop’s beloved sign red, despite her assurances of profits. Nonetheless, no sooner does a Chinese investor offer Nancy a healthy sum to buy her shop than—uncomfortable with the change in her clientele brought by the bus tours—she decides to accept it.

More oil gets poured on these troubled waters by a plan to turn the factory into a hospital specializing in Chinese medical procedures, which inspires such racial animosity that the place is ridiculed as a “Chink hospital.” When Nat uses that word, we even get a kindly lecture to him by his mom about using such hurtful terms. Personally, I thought “Chinks” went out in the 1960s, when people switched to eating “Chinese” food.

Pierce’s uneasy mash-up of romantic comedy, urban political satire, anti-racist advocacy, and even—out of nowhere—gun violence lacks an organic, truthful feel blending honest acting with vital storytelling. We’re asked to buy barely explained plot developments like Lydia’s becoming the owner of the factory despite being deeply in debt, or the un-foreshadowed appearance of a firearm and the vaguely conciliatory conclusion to which it leads.

Derek McLane’s spacious but dreary unit set, in which all the scenes transpire by having the usual headset-wearing stagehands shove things on and off in the dimness, represents a 19th-century factory’s gray, brick walls. At first, though, I wondered if it were a prison or, perhaps, because of the desk and American flag in the first scene, an old school.

Amith Chandrashaker’s lighting only manages to successfully alter the scenery’s dull efficiency when he introduces a red wash during the episodic play’s scene changes. Jennifer Moeller’s costumes are appropriate, Leah Gelpe’s sound is unobtrusive, and J. David Brimmer offers a touch of his distinguished fight direction expertise.

Call it cardinal or call it red, hopefully, it’s your favorite color because you’ll be seeing lots of it during this production.

“Did the Folks Next to Me Like It?” (2)

Often, I’m very aware of how the strangers sitting next to me at a show are reacting. I may hear the audience laughing across the way or behind me, while the man or woman beside me is sitting stone-faced. Or I may notice sniffling while I myself am falling asleep. Since I often wonder how they feel about what we’ve both just experienced I’ve decided to simply ask them and record their reactions by giving the show an on-the-spot grade on the scale of 1-100. Herewith, my apologies to the “Did He Like It” website.

My plus-one and I were the only people in our row at Cardinal so I tapped the shoulder of the nearest person, a silver-haired, cane-assisted, elderly lady—the sole occupant of the row in front of me—and asked her for a grade: “56,” she quickly replied, asking in turn for mine. “Somewhat lower,” I answered, and, smiling, she shook her head in assent.

OTHER VIEWPOINTS:

Second Stage Theater/Tony Kiser Theater

305 W. 43rd St., NYC

Through February 25