"A Gay Romance"

There’s no denying that Midnight at the Never Get, a new musical with book, music, and lyrics by Mark Sonnenblick, and “co-conceived” by one of its stars, Sam Bolen, has its heart in the right place. Which is not to say it’s entirely free of blockages.

There’s no denying that Midnight at the Never Get, a new musical with book, music, and lyrics by Mark Sonnenblick, and “co-conceived” by one of its stars, Sam Bolen, has its heart in the right place. Which is not to say it’s entirely free of blockages.

|

| Photo: Carol Rosegg. |

It tells the fictional love story of two gay musical artists,

Arthur Brightman (Jeremy Cohen), a coolly detached, New York songwriter, and

Trevor Copeland (Bolen), an emotionally needy young lounge singer who grew up

on an Idaho farm. We watch as they navigate their love and careers against the

changing world of gay identity politics from the 1960s on.

Its narrative premise, which isn’t always crystal clear, is

incorporated into a fantasy concept wherein Trevor’s spirit is emceeing a show in

an afterworld version of the Never Get, a 1960s Greenwich Village gay bar,

illegal at the time. This is where he and Arthur first gained notice in late night

gigs they called Midnight at the Never Get.

What we’re seeing, though, is happening now. Trevor, who died

years before from what we’re led to assume was AIDS, is waiting for Arthur, who

has just passed, to arrive so he can help fill or revise the gaps in Trevor’s

memory. The show presents Trevor’s memories of their affair, from when they met

in 1965 to when their relationship dissolved.

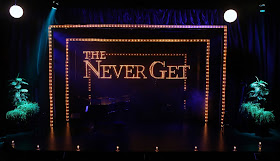

Two-thirds concert, one-third play, Midnight at the Never Get is presented against the eternally smoky

background of a cabaret stage (designed by Christopher Swader and Justin Swader),

outlined in marquee lighting, with the words THE NEVER GET illuminated across the

upstage wall.

As neatly directed by Max Friedman, the Arthur that Trevor

remembers sits at a piano, in black tie and tux, rising only occasionally, conversing,

and sometimes singing, with the maroon-tuxedoed Trevor (costumes by Vanessa

Lueck). Arthur’s presence continually fades in and out via the deft lighting of

Jamie Roderick. Toward the end, a surprise character (John J. Peterson) appears.

He adds a bit of variety but I was never convinced he had to be there in the

first place.

The emotionally rich but melodically not-quite-there songs

are the results of Sonnenblick’s attempt to capture the American songbook quality

associated with the sophisticated compositions of Cole Porter and his ilk. A few,

like “The Mercy of Love” and “Dance with Me,” stand a bit apart, and, in a

shift from the constant emphasis on romantic love, there are amusing lyrics and

a pleasant bounce to “My Boy in Blue,” a comic paean to hooking up with a

handsome cop.

Generally speaking, though, the lyrics and music, while superficially

pleasant, and definitely well performed, sound like so-so pastiches of 40s and

50s numbers, struggling to emulate the standards but too often falling short. Certainly,

they never reach the level of material you’d want to sing along with to the

voices of Connie Francis and Eydie Gormé, whom the script references as singers of Arthur's songs.

Sonnenblick’s dialogue observes that this general type of music

(of which Trevor notes: “Cole Porter had written these songs thirty years ago

and better”) was being outpaced at the time by rock. Arthur even pokes fun at rock

music by referencing the Beatles’ “I Wanna Hold Your Hand”:

“Are you kidding me? That’s not a lyric that’s a note you pass in kindergarten.”

To which one might respond, “Are you kidding me?” Would that

just one of the songs in Midnight at the Never

Get were half as catchy as Lennon and McCartney’s kindergarten note. Still,

for all his disdain of such things, Arthur gradually finds success on his own

terms, especially after moving to L.A., where his career takes off and his sexual

preferences take a detour.

To give the material a sense of verity, Sonnenblick drops real

people’s names (see the aforementioned Gormé and Francis) into the mix, just as he mentions such real 60s

nightspots as the Blue Angel, the Café Wha, and the Bon Soir. Of course, the Stonewall

Inn is cited, along with its place in the evolving gay pride movement,

providing the historical background against which Arthur and Trevor’s issues intensify.

The strains in the men’s romance, such as they are, touch on

Arthur’s distaste for the more public expressions of gay identity, including personal

behavior and involvement in activist marches, and the more open ones of Trevor.

Such conflicts also involve the problem of the personal pronouns in Arthur’s

male-male oriented songs, both when Trevor sings them publicly to disapproving

audiences and when record execs demand they be changed for public consumption.

Sam Bolen’s Trevor is personable, energetic, and expressive, sometimes in a mildly campy way, with a fine voice that takes full advantage of the soaring notes Sonnenblick often provides. Jeremy Cohen offers a nice counterbalance with his more somber, taciturn presence. His singing and piano playing give the show a necessary grounding, as do the high-quality orchestrations of Adam Podd, especially when the excellent five onstage musicians (drums, trombone, alto sax/clarinet/flute, trumpet, and bass) kick in and almost succeed in making Sonnenblick’s ordinary music sound more extraordinary than it is.

Midnight at the Never

Get provides a mildly diverting hour and a half of gay-oriented musical

theatre. It hits a few significant historical notes but, without an especially

memorable score or a more satisfying plot, dawn sometimes a long time coming.

OTHER VIEWPOINTS:

York Theatre (at Saint Peter’s Church)

619 Lexington Ave. (entrance on E. 54th St.), NYC

Through November 2