|

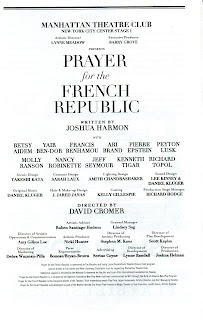

| Francis Benhamou, Jeff Seymour, Yair Ben-Dor, Betsy Aidem. (Photos: Matthew Murphy.) |

If there’s one thematic word that sums up the general impression of the 2021-2022 Broadway and Off-Broadway season thus far, it’s racism. By and large, that theme has been embedded in plays about African-American issues, from Pass Over to Slave Play to Black No More. Even The Merchant of Venice, about a Jewish merchant, has dipped its toes in these muddy waters by casting a Black actor as Shylock in a play dealing with anti-Semitism (some think it’s anti-anti, others that it’s pro-anti). Jews, of course, are not a race, but a religion, yet few dispute that anti-Semitism falls within the parameters of racism. Anyway, Jewish Lives Matter.

All of which leads us to the Manhattan Theatre Club’s

production of Joshua Harmon’s (Bad Jews) stimulating if overblown play about

anti-Semitism, Prayer for the French

Republic, downstairs at the City Center. The play’s premise can be summed

up in one sentence: In 2016 France, a French Jewish family is so disturbed by

the growing outbursts of violence against Jews (the 2015 Charlie

Hedbo shooting is one of many) that it considers moving to Israel. This

basic situation is so fraught with personal and political vibrations, however,

that Harmon has turned it into a three-act, three-hour play. Consequently, this

allows for more expansive coverage of its issues while simultaneously weakening

its dramatic impact.

|

| Mary Robinette, Kenneth Tigar. |

The setup, introduced by the cynically nonobservant,

middle-aged Patrick Salomon (Richard Topol), who serves throughout as narrator,

is this: Patrick’s moderately observant sister, Marcelle (Betsy Aidem), a

psychiatrist, and her husband, Charles Benhamou (Jeff Seymour), a physician and Algerian

refugee, live in a Paris apartment with their youthful but grown children.

Daniel (Yair Ben-Dor) is a math teacher at a Jewish school, and Elodie

(Francis Benhamou) is very smart but manic depressive. Marcelle and Patrick are the offspring of Pierre Salomon (Pierre Epstein), an

octogenarian seller of pianos whose family has been in that line—their names

are on the pianos—for generations, going back to the mid-nineteenth century. A

Salomon piano dominates the set.

|

| Richard Topol. |

Visiting is a distant American cousin they’ve never met, a

young woman named Molly (Molly Ranson), fluent in French but there for a year

to learn it even better. Soon after the opening exposition introduces us to

Molly and Marcelle, Charles and Daniel enter, the latter’s face bloodied by an

encounter with anti-Semitic thugs who apparently targeted him because he wears

a kippah (yarmulke). (In one of the more formulaic plot developments, Molly and

Daniel will have an incipient romance.)

|

| Molly Ranson, Francis Benhamou. |

Soon we’re embroiled in conversations and arguments about

what it means to be Jewish, what it means to be French, the relative piety or

secularism of the characters (Daniel being the most religious), whether one

should flaunt one’s beliefs by outward signs (Daniel’s kippah), the rise of

right wing extremist Marine Le Pen, the defeat of Hillary Clinton, and so on.

Also lighting fires are disagreements about personal safety, whether the family

or members of it should move to Israel, the pros and cons of Israeli politics,

the degree of security one can expect in the Middle East, the difficulty of

starting over in a new country, and so on.

|

| Betsy Aidem, Richard Topol, Pierre Epstein, Francis Benhamous, Jeff Seymour. |

Perhaps because he wants to expand the situation to

demonstrate the family’s deep roots in France, Harmon uses flashbacks to the

years 1944-1946 (during and right after the Nazi occupation) to show Marcelle

and Patrick’s great-grandparents, Irma (Nancy Robinette) and Adolphe (Kenneth

Tigar), their grandfather, Lucien (Ari Brand), and their father, his son, the

young Pierre (Peyton Lusk). As noted, the latter appears as an old man, late in

the play. These scenes have a certain interest in filling in family history, and

explaining how they escaped Nazi extermination, but they also tend to bog the episodic

play down and draw it out longer than need be. To help connect these scenes to

the present, Patrick, like the Stage Manager in Our Town, serves as an onlooking interlocutor, who also takes

considerable time to explain the history of Jewish oppression in France, with

vivid descriptions of the suffering people endured. In preparation for writing

the play, Harmon traveled to France to do research. The results show.

|

| Molly Ranson, Jeff Seymour, Yair Ben-Dor. |

The play works best when situated in the 2016 apartment where the mildly dysfunctional Benhamou family, their guest, and—when he takes part in a Seder—Patrick, are present. The family is deeply loving, virulently contentious, but wittily sardonic, providing welcome leavening to the overall seriousness. Elodie, for example, vehemently challenges as anti-Zionist the politely critical comments made by the liberal American visitor she’s just met. Without explanation for the shift, however, she later spews her polemics, geyser-like, to Molly as if someone magically removed the chip from her shoulder.

|

| Mary Robinette, Kenneth Tigar, Ari Brand, Pierre Epstein, Peyton Lusk, Richard Topol, |

Essentially, this is good old discussion drama, where disagreements strike sparks that make you question your own beliefs. Harmon often succeeds at taking both sides so that you don’t feel as if he’s putting his thumb on the scales, at least not too heavily. And his dialogue and situations are always richly stage-worthy without going over your head. Prayer for the French Republic sometimes borders on situation comedy so you occasionally laugh at awful things, including allusions to similar events in the U.S.A.

Designer Takeshi Kata, using sliding units and a revolving

stage, allows for multiple shifts from scene to scene, giving the play a

cinematic flow, although the apartment décor itself is rather bland. Sarah Laux’s believable costumes and Amith Chandrashaker's atmospheric lighting do nicely without drawing attention to

themselves, and director David Cromer gets quality performances from his ensemble.

There is, however, very little French atmosphere about the

production. The actors speak colloquial English, with lots of “bullshits” and “fucks,”

and the overall tone is undeniably American. (I imagine a British production

would sound equally British.) This is a problem built into having a playwright

of one nationality writing a play about another where the people all speak a

foreign language. Is the answer to have them all use accents? That, too, can go

seriously wrong. Perhaps there is no answer, but it definitely is a minor

distraction, less apparent in translations from foreign languages than plays

written as if in those languages.

Prayer for the French

Republic, which takes its title from a prayer—spoken in the play—that has

been part of French Jewish services for a couple of hundred years, is a worthwhile addition

to the season. A tighter structure, including rethinking the inclusion of the

1940s scenes, would help greatly; even with them, though, audiences are likely

to find much here to appreciate and from which to learn.

Prayer for the French Republic

City Center Stage I

131 W. 55th Street, NYC

Extended through March 13