"Noh News Is Good News"

|

| Stars range from 5-1. |

This year marks the 70th anniversary of the end of World

War II, in commemoration of which the Japan Society thoughtfully programmed three

theatrical presentations on the theme of “Stories of War.” The third and final

one, given three showings at the Japan Society this weekend, from May 14 to May

16, was of two noh plays, KIYOTSUNE, a traditional one dating from the 14th

century, and a modern one, HOLY MOTHER IN NAGASAKI, first staged in 2005.

Few world theatre forms are as capable as noh at

embodying solemnity and spirituality. Noh is one of Japan’s four principal

forms of traditional theatre, the others being kyōgen, kabuki, and bunraku. It

took its essential form in the 14th and 15th centuries, and became the favored

ceremonial theatre of the samurai class during the Edo period (1603-1868). It is a serious, highly formalized

style of theatre, often dealing with Buddhist themes of life’s transience and

the search for spiritual salvation. Kyōgen, which came into existence around the same time

as noh, is a mostly comic form of theatre that, traditionally, was performed

between noh plays on a multiplay program. Many noh plays include a kyōgen character who speaks in a more colloquial language than the highly formalized one of the leading personages. Kabuki and bunraku are popular types

of theatre that arose at the turn of the 17th century and were attended mainly

by urban commoners. Their plays often show the influence of noh and kyōgen.

Noh is performed on specially designed wooden stages (either

indoors or out), with the audience seated on two sides; they employ specific

features, such as four pillars that support a gabled roof, a long bridgeway

leading from the upstage right corner to offstage, and a back wall on which is

painted the image of a pine tree. When touring abroad, modifications must be

made; thus the Japan Society performances are on a proscenium stage backed and

bordered by black drapes; the pillars marking the borders of the acting area

are abbreviated in size and serve mainly as markers, and a low wooden border upstage left suggests where a conventional bridgeway would be.

Noh plays are always accompanied by an onstage chorus

seated in two rows at stage left; typically, the chorus has eight singers, but

for this tour only six are used. Such adjustments are normal and barely affect the

quality of the work.

|

| KIYOTSUNE. Shimizu Kanji. Photo: Julie Lemberger. |

KIYOTSUNE, which opened the program, is the work of

the master actor-theorist-playwright Zeami Motokiyo (1363?-1443?) and belongs

to the second of the five groups into which classical noh

plays are divided. These plays are often called shura (or asura) noh because

they deal with samurai who fell in battle and are suffering in the Buddhist

hell called shura. The principal

character is usually a ghost who appears in his living form to a priest at the

scene of the battle in which he died. He then leaves and returns as his ghostly

self to describe the torments he’s experiencing in hell and to seek salvation.

In KIYOTSUNE, however, which takes its name from its

principal character, an actual historical figure, the ghost of Kiyotsune (Shimizu Kanji) appears in the dream

of his widow (Tanimoto Kengo). KIYOTSUNE has several interesting anomalous

features for a second group play; aside from noting that there is no priest involved and that the play is in a single act, not two, we can skip them here and simply observe that Kiyotsune, a general in the once all-powerful Heike clan (rivals of the Minamoto clan), while engaged in

the Battle of Tsukushi, chose to commit suicide by drowning rather than allow

himself to be killed or captured by the lowly enemy. When his wife learns of

how he died, from a retainer (Tonoda Kenkichi) who brings her a lock of his

hair as a keepsake, she is both sad and angry, the latter because she would

have preferred that he died in battle or from illness, not by suicide. She falls asleep

and Kiyotsune appears in her dream, where they bicker, both over the manner of

his death and her rejection of his keepsake; he had left it to console her but

all it did was increase her anguish. He sings and dances the story of his death

and why he acted as he did. Finally, after recounting the pains of hell, he

finds salvation in the Western Paradise.

|

| HOLY MOTHER IN NAGASAKI. Shimizu Kanji. Photo: Julie Lemberger. |

The modern play, HOLY MOTHER IN NAGASAKI, by the late Dr. Tada Tomio (1934-2010), a respected immunologist, is one of two he wrote focused on

the atomic bombing of Japan (the other was about Hiroshima). Although there are roughly 250 plays in the

traditional repertory, many more were written that fell by the wayside. In the

20th century, a movement to write new noh (and kyōgen) plays took root, and

even Westerners attempted to write such plays of their own, with subjects as

diverse as Martin Luther King, Jr., Saint Francis of Assisi, and the Japanese

naval dead of World War II. Many modern noh plays are based on the materials

and methods of classical noh, and others use traditional materials but treat

them with a modern touch, while others take their themes and materials from

modern subjects and/or foreign sources. Among the best-known modern noh plays

is 1991's controversial THE WELL OF LONELINESS (Mumyō no I), also by Dr. Tada, about brain death and a heart transplant, while others have

adapted Shakespeare’s plays, like OTHELLO, MACBETH, and HAMLET to the noh

style.

HOLY MOTHER IN NAGASAKI (Nagasaki no Seibo) was

inspired by the August 9, 1945, atomic bombing of Nagasaki, among whose

destroyed buildings was the Urakami Cathedral. Nagasaki has long been the

center of Japanese Catholicism. The play’s 2005 premiere was at the rebuilt

cathedral, where many parishioners were killed by the bomb while at mass. Shimizu

Kanji played the Virgin

Mary in that and subsequent productions, just as he did in this one at the Japan Society.

The play is, in part, a history lesson about the Urakami

Christians, who had to go into hiding after Japan banned Christianity in the

early 17th century but who were once more allowed to practice their religion in

1873. It is also a requiem for those killed in 1945 and a soulful, prayer for world peace and nuclear disarmament.

It imagines a pilgrim (Tonoda Kenkichi) arriving at the cathedral, where he expresses

regret for the sufferings of the Urakami Christians, whose souls he wishes to comfort,

and learns from priest (Ogasawara Tadashi) the details of the bombing. The priest,

much like “the man of the place,” a conventional character in many noh plays performed

by a kyōgen actor, describes the horrors of that fateful day, recalling a

mysterious woman (Mr. Shimizu) who appeared in the evening to care for the

injured and dying. She, it was assumed, must have been the Virgin Mary.

HOLY MOTHER IN NAGASAKI has most of the trappings of a

noh play: its language is in the archaic, premodern noh style (except for the priest’s kyōgen-like vernacular); it uses a chorus (although not as extensively as a

standard noh play); and there’s a four-piece

noh orchestra upstage (KIYOTSUNE uses only three musicians). The scenery is limited to a simple, fabric-covered platform, a large but

simple crucifix hanging on the upstage wall, and two electrified standing lamps resembling candle holders. Costumes, apart from the priest, who wears a black cassock, are in the

14th-century mode, and the Virgin Mary--dressed in a striking red robe, embroidered in gold--wears both the noh mask of a young woman

and a wig of flowing black hair. One might argue that there’s a

disconnect between the modern and traditional elements of language and costuming, but the effect is insignificant.

Adding to the spiritual atmosphere at this production was the deeply moving use of

Gregorian chant, sung from the rear of the theatre at the beginning and end by the all-female Choir of the Church of St. Francis Xaviar, New

York City, conducted by John Uehlein.

Both plays were performed in Japanese with English subtitles flashed on projection screens at either side of the stage.

NEW AND TRADITIONAL NOH

Japan Society

333 East 47th Street, NYC

May 14-16

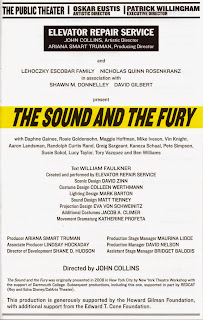

For my review of THE SOUND AND THE FURY, please click on THEATER PIZZAZZ.

For my review of THE SOUND AND THE FURY, please click on THEATER PIZZAZZ.

Simon

Callow* is one of those classically trained British actors whose little finger

knows more about acting than most thespians do in their entire bodies. He’s now

putting that knowledge to work in this slim but performance-challenging

monodrama (supplemented by an onstage pianist, Conor Mitchell), in which he

plays a transgendered woman called Pauline (formerly Paul). He wears a limp

blonde wig, an unflattering beige outfit, turquoise high heels, turquoise earrings,

a turquoise cinch belt, and a red-orange blouse offering a touch of décolletage; nonetheless, the decidedly thickening, masculine-featured 65-year-old star speaks in what is surely one of the theatre’s most posh and plummy baritones.

Simon

Callow* is one of those classically trained British actors whose little finger

knows more about acting than most thespians do in their entire bodies. He’s now

putting that knowledge to work in this slim but performance-challenging

monodrama (supplemented by an onstage pianist, Conor Mitchell), in which he

plays a transgendered woman called Pauline (formerly Paul). He wears a limp

blonde wig, an unflattering beige outfit, turquoise high heels, turquoise earrings,

a turquoise cinch belt, and a red-orange blouse offering a touch of décolletage; nonetheless, the decidedly thickening, masculine-featured 65-year-old star speaks in what is surely one of the theatre’s most posh and plummy baritones.

Before you

can take your seat at the tiny Theater C at 59E59 Theaters you have to pass the

small stage on which, sitting on a red leather-covered trunk, is a pretty blonde,

smartly dressed (costumes are by Meriel Pym) in late 50s style, mink coat and

all. This is Janet Shirley (Eve Burley), the heroine of Anthony Burgess’s ONE

HAND CLAPPING, a 1961 satirical British novel newly adapted and directed for

the stage by Lucia Cox and now visiting New York as part of the Brits Off

Broadway festival. The production was originally given by the House of Orphans in Manchester, UK.

Before you

can take your seat at the tiny Theater C at 59E59 Theaters you have to pass the

small stage on which, sitting on a red leather-covered trunk, is a pretty blonde,

smartly dressed (costumes are by Meriel Pym) in late 50s style, mink coat and

all. This is Janet Shirley (Eve Burley), the heroine of Anthony Burgess’s ONE

HAND CLAPPING, a 1961 satirical British novel newly adapted and directed for

the stage by Lucia Cox and now visiting New York as part of the Brits Off

Broadway festival. The production was originally given by the House of Orphans in Manchester, UK.