74. LOVE LETTERS

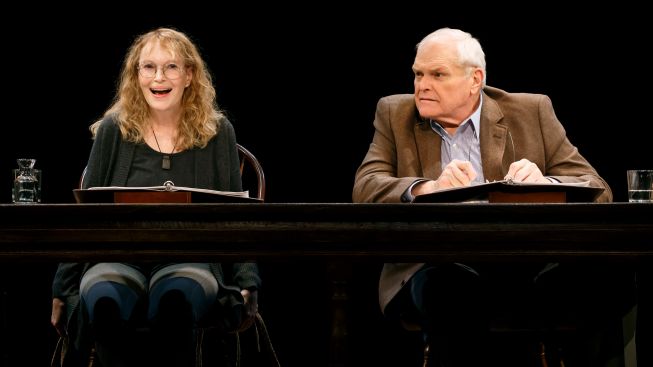

OMG and LOL are not in the lexicon of Andrew Makepeace Ladd III and Melissa Gardner, the protagonists of LOVE LETTERS, A.R. Gurney’s profoundly poignant yet often hilarious epistolary play, now in revival at the Brooks Atkinson Theatre. But OMG, I loved it, and, as superbly performed by Brian Dennehy and Mia Farrow (more than superb, actually), I both LOL and found myself ‘-( during its captivating presentation.

LOVE LETTERS, first presented at New Haven’s Long Wharf Theatre in 1988, with John Rubenstein and Joanna Gleeson, and afterward produced at New York’s Promenade Theatre with a succession of famous actors playing the leads, moved the same year to the Edison, a small Broadway theatre, where the practice of different stars taking over the parts during the run continued. It has had numerous productions since, often for one-night stands, because all it needs are two actors, a stage or platform, a table, and two chairs. The actors read from scripts so they don’t even have to memorize their lines. [Correction: An earlier posting of this review noted that the Edison was technically Off Broadway. According to Wikipedia, the Edison, now gone, had 541 seats, which would qualify it as a Broadway house, but it also could do plays using 499 seats, making it Off Broadway. LOVE LETTERS ran as a Broadway show. I have revised the review to reflect this, with thanks to Prof. James Wilson of CUNY for his input.]

|

| Mia Farrow, Brian Dennehy. Photo: Carol Rosegg. |

The piece now is getting its first production in a major Broadway theatre, the Brooks Atkinson, where it’s been directed by Gregory Mosher. Despite the minimal requirements of set, lighting, and costumes, each design area has been assigned to a leading designer, John Lee Beatty for the first, Peter Kaczorowski for the second, and Jane Greenwood for the third. (For the Edison production Mr. Beatty was “scenic consultant,” and there was no costume designer.) As for the casting, after Ms. Farrow departs, she’ll be replaced by Carol Burnett, playing opposite Mr. Dennehy, and they’ll in turn be followed by Alan Alda and Candice Bergen, who’ll give over to Stacy Keach and Diana Rigg, while Anjelica Huston and Martin Sheen will come after them. A program insert promises “many more brilliant casts to be announced.” I admit to having been so taken by the performance I attended—even though I could see bits and pieces of only about 10 of its 90 minutes because of a horrendous sightline problem—that if time and finances allowed, I’d come back and see each new pair of players. (More on the sightline issue later.)

It could be argued that LOVE LETTERS is really a radio play (which is essentially how I experienced it), since Mr. Gurney explicitly calls for no physical interplay between the actors. In a note published with the script, he says: “the piece would seem to work best if the actors didn’t look at each other until the end, when Melissa might watch Andy as he reads his final letter. They listen eagerly and actively to each other along the way, however, much as we might listen to an urgent voice on a one-way radio, coming from far, far away.” When I saw it, Mr. Dennehy didn’t look at his partner at all, but Ms. Farrow did, for a brief moment, glance wistfully at him. But listen they did, closely.

Over the course of the play, performed without a break despite Mr. Gurney’s script suggestion that one be taken midway through, we hear the actors read the letters, cards, and notes that Melissa and Andy have mailed or passed to one another from the time they were childhood friends and classmates. In a sense, the play is a paean to the days when people put pen to paper and stuffed these papers in envelopes, on which they placed a stamp, then put them into mailboxes, and waited impatiently for similarly created replies.

I recently came across such a missive from my kid brother, sent to me from Brooklyn after I’d gone off to grad school in Hawaii over 50 years ago, telling me how much he missed me and begging me to write more often; despite (or possibly because of) its writing errors, its power to evoke a time and place in our lives floored me. Why did I ignore him? Was it because I was writing so many letters to my girlfriend, letters that would so grow in frequency and intensity that our love grew exponentially to where we agreed for her to fly to Honolulu so we could marry? I suppose many of us from an older generation have such letters somewhere, saved in shoeboxes or whatnot. We may not bother reading them, but they’re there, tangible reminders of our existence at specific moments in our lives. When, for some reason, we do open them, especially the forgotten ones, the experience can be overwhelming. How many of us plan to print out our e-mails (or texts!) so we can return to them 50 years hence?

The relationship between Mr. Gurney’s New England-raised children of privilege (she being much richer than he) covers 50 years, starting in the late 1930s, during which their jottings reveal their gradual maturing, as they progress through all the stages of elite private schools, college, and on into their post-college years. Signs of trouble in Melissa’s youth emerge in contrast to the picture of Andy as an upright, socially conscious, studious young man, whose rectitude and submission to his parents’ wishes Melissa often criticizes. We gradually see the effect on Melissa of her mother’s marital problems and alcoholism, which leads eventually to her own excessive drinking, romantic difficulties, and psychological crises.

The subtextual love between these devoted friends, throughout their tiffs, misunderstandings, and mutual reprimands, is revealed bit by bit in their written comments, some merely a word or two in length, others more extensive. Despite their mutual affection, true romance fails to unite them and they gradually go their separate ways, but they never do lose touch (something like what Facebook is now helping to restore); even though much time passes between their letter-writing connections, they remain deeply attached to one another. Love affairs and marriages, careers (she becomes an artist, he a lawyer and politician), and the rest of life’s milestones come and go, until, eventually, their lives reunite, if only fitfully and with keenly moving results that affect me whenever I recall them.

Despite the marvelous sensitivity of Mr. Gurney’s writing, which so exquisitely captures the tone, attitudes, thoughts, and experiences of these well-heeled WASPs, the pangs I feel when thinking of LOVE LETTERS in performance stem greatly from the extraordinarily touching performance of Ms. Farrow as Melissa. Looking (when I managed to see her) every bit as luminous as she’s always been on screen, her crinkly, shining blondeness framing her delicate facial features, seen behind large, round eyeglasses, she manages to be funny, sad, angry, wise, silly, frightened, and fragile with total believability. As Melissa grows psychologically troubled, the desperation and need in Ms. Farrow’s voice cut into your heart so pitifully because it was only minutes earlier that you saw her as a sweet, although not guileless, and endearing child. The loss of innocence she evokes is truly heartbreaking.

The burly, gray-haired, and bespectacled Mr. Dennehy, in the less flamboyant role, again demonstrates his vaunted stage power and presence, as he takes us through Andy’s life, from diligent, respectful schoolboy to teenager with a crush to wartime service to success as a high-powered lawyer and senator. Always, even in his maturity, he retains Andy’s appealingly boyish goodness, and we truly feel for his dilemma when, late in life, he finds himself painfully enmeshed with the deteriorating sweetheart of his youth.

I noted earlier that my visit to LOVE LETTERS was marred only by my inability to see much of it. I had an otherwise quality seat in row H, but the placement of the table downstage seems to have been done without recognizing how spectators in the poorly raked auditorium could view it. The simple solution of placing the table on a slightly raised platform seems not to have occurred to anyone. If you plan to see this wonderful piece of theatre, and want good seats, I’d advise you to get them in the rear of the orchestra or, better yet, the front mezzanine. Amazingly, though, even if you just listen to the actors, as if they’re on the radio, you’ll be more moved and charmed than at many other plays more lavishly produced. At least I was.