|

| Sheila Smith (left, with baton), Tony Roberts, Robert Morse, and company |

SUGAR [Musical/Crime/Period/Romance/Show Business] B: Peter Stone; M: Jule Styne; LY: Bob Merrill; SC: Billy Wilder and I.A.L. Diamond’s screenplay, Some Like it Hot (from a Robert Thornton story); D/CH: Gower Champion; S: Robin Wagner; C: Alvin Colt; L: Martin Aronstein; P: David Merrick; T: Majestic Theatre; 4/9/72-6/23/73 (515) |

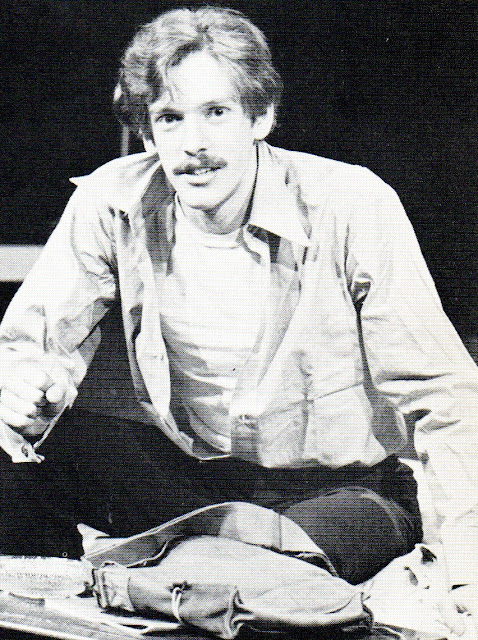

| Cyril Ritchard, Tony Roberts. |

A musical version of Some Like It Hot, the ever-popular, crossdressing, 1959 film farce, set in the Roaring Twenties, in which Elaine Joyce, Tony Roberts, and Robert Morse took the roles immortalized on screen by Marilyn Monroe, Tony Curtis, and Jack Lemmon. It came into New York after expensive out-of-town revisions, including the replacement of the book writer, as well as of both the set designer and his set. Cast changes and production doctoring were other remedies applied to the ailing show.

|

| Robert Morse, Tony Roberts, Sheila Smith (right) |

For all its troubles, the show had a fairly robust run while failing to satisfy many critics. For most, it was an elaborate, colorful show of what Julius Novick deemed “deeply mediocre” quality. It was, he added, “smooth, polished, professional, safe, and not very interesting.” “It doesn’t work as a musical,” claimed Clive Barnes, who, like various others, thought its performances the chief reason for a visit. Sugar, he remarked, “Had a dearth of jokes, a shortage of wit and a scarcity of verbal humor that is almost remarkable.” John Simon, on the other hand, believed its many weaknesses were made up for by its being “the most diverting, stylishly mounted, smoothly acted, brilliantly staged and endearingly danced [non-musical musical] in many a season.”

Composer Jule Styne and lyricist Bob Merrill, both Broadway A-listers, were accorded little but condescension for what Brendan Gill labeled their “workmanlike and old-fashioned” score, Walter Kerr, however, found pleasure in the music’s authentic period sound and in the energetic title song. The other numbers were “Windy City Marmalade,” “Penniless Bums,” “Tear the Town Apart,” “The Beauty that Drives Men Mad,” “We Could Be Close,” “Sun on My Face,” “November Song,” “Hey, Why Not!,” “Beautiful Through and Through,” “What Do You Give to a Man Who’s Had Everything?,” “Magic Nights,” “It’s Always Love,” and “When You Meet a Man in Chicago.”

|

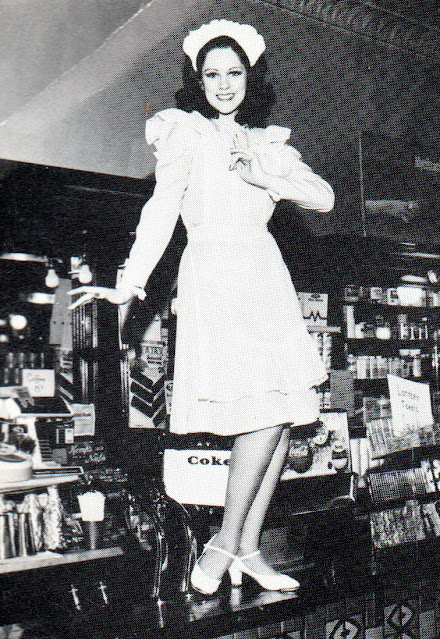

| Robert Morse, Elaine Joyce. |

The familiar plot tells of two jobless Chicago musicians, Jerry (Morse) and Joe (Roberts), who are on the lam after witnessing the infamous St. Valentine’s Day Massacre. They disguise themselves as performers in an all-girl band, where each falls for singer Sugar Kane (Joyce), a simpleminded blonde with her heart set on marrying a millionaire. In the course of the action, a rich old lech (Cyril Ritchard, Joe. E. Brown in the movie) pursues Jerry, thinking him female, of course, with intentions of marriage. Ultimately, the pursuing gangsters are disposed of and Joe gets Sugar.

The attractive Elaine Joyce and the appealing Tony Roberts were sweetly but not very enthusiastically received. Robert Morse’s performance, despite being slapped for too much mugging, was the big attraction, especially for a hilarious scene in which Ritchard tried ardently to seduce him.

Master showman Gower Champion’s work, which inspired Simon to comment that it “was one of the few consummate pieces of musical staging I have witnessed,” demonstrated great inventiveness in many routines, like the staccato tap dance performed by chief gangster Spats Palazzo (Steve Condos). On the other hand, it was noted that Champion offered insufficient musical staging for the singing numbers. T.E. Kalem, unimpressed, thought “the dances could be inserted in another musical, where they would mean no more and no less than they do in Sugar.”

Despite bland notices, Sugar entertained audiences for over 500 performances. It received Tony nominations for Best Musical; Best Director, Musical; Best Choreographer; and, for Morse, Best Actor, Musical. Elaine Joyce won a Theatre World Award.

Next up: Sugar Mouth Sam Don’t Dance No More and Orrin