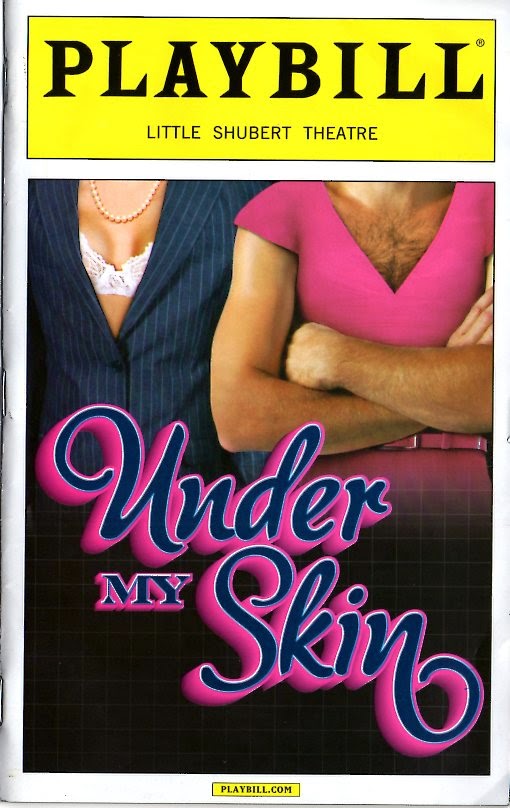

16. UNDER MY SKIN

UNDER MY SKIN, a gender-swapping farce that opened recently at the Little Shubert Theatre, is tacky, staged with sledgehammer subtlety, and acted like a thespian version of Hurricane Sandy. It’s also intermittently funny and sexy, and it even deals with a socially important subject, health care insurance. The husband and wife playwrights, Robert Sternin and Prudence Fraser, are highly successful sitcom writers; they developed “The Nanny” for Fran Drescher, whose experience with uterine cancer in 2000 inspired part of UNDER MY SKIN’s plot. The female lead in this derivative piece may not come from Queens, but her Staten Island accent isn’t that far different from Fran Fine’s on “The Nanny.”

Harrison Badish III (Matt Walton, very good) is the hunky, greedy, and arrogant CEO of Amalgamated Healthcare, whose bottom line takes precedence over the actual needs of its customers. Among the female employees who lust for him is part-timer Melody Dent (Kerry Butler, appealing), a Staten Island divorcée who cares for her dementia and diabetes-stricken grandpa, the kvetching Poppa Sam (Edward James Hyland) and her rebellious teenage daughter, Casey (Allison Strong). Melody and Harrison are in the elevator when it suddenly crashes 14 floors, killing them both (and providing a clever scenic effect). An overweight female angel in white named Angel (Dierdre Friel, funny) appears to inform them of their fates, but they convince her to bring them back to life. She knows she can do it because she’s done it before: “It worked on Liza Minnelli.” However, an error occurs in the Department of Eternal Affairs and, when Harrison and Melody survive, he’s in her body and she’s in his. The actors merely don clothing resembling the other person’s; only the audience can see that the muscular guy in the dress is Melody and the gal in the men’s garb is Harrison. The device takes some getting used to, but it leads to some risqué comic business, such as when the diminutive Melody, wearing Harrison’s sweat pants, gets aroused and a visible bulge grows in her crotch.

Harrison has a luscious but bitchy brunette girlfriend, Victoria (Kate Loprest), whose presence provides inspiration for some sexually mixed-up bedroom activity, with Melody experiencing intercourse from a male perspective. After being fellated, she remarks: “Now I know why they all want that.” There’s considerable byplay surrounding her seemingly inadvertent erections, of which she says: “It does it by itself.” Each audience member will have to deal with this material based on their own comfort level, but there’s no denying there’s a yucky factor mixed in with the yucks. Similarly, the scene where Harrison, in the guise of Melody, has a gynecological exam (from Dr. Hertz, hardy har har) may cause goose bumps.

Kerry Butler, Kate Loprest. Photo: Joan Marcus.

The exam provides a springboard for satirical commentary on health care insurance inequities, and leans toward unexpected seriousness when Melody (Harrison, that is) discovers that she has cancer. Of course, everything works out for the best, and, again through the ministrations of Angel, the gender confusion gets straightened out, Harrison has an epiphany about health care reform, and the expected romantic conclusion arrives. Even Melody’s oversexed BFF Nanette (Megan Sikora; yes, there’s a “No, no, Nanette” crack), who’s as hot to trot as California Chrome, is able to put her considerable assets (accent: first syllable) to good use as the show reaches its, ahem, climax.

Most of the actors play multiple roles, sometimes shifting from one to another without any effort to hide the transition. Kirsten Sanderson has directed everyone to speak at the top of their voice and to overdo their cartoonish behavior. For example, Ms. Sikora, who clearly has comic potential, shrieks many of her lines and seems to think it necessary for her voluptuous body to be a human semaphore to all men at sea. She does have a great moment, though, when, wearing only her scanty undies, she manages the seemingly impossible task of wiggling into a skintight sheath (naturally, everything she wears is skintight and I wouldn't have it otherwise).

This is one show that would have worked better in a smaller venue. The Little Shubert, despite its name, is capacious, and the various locales of Stephen Dobay’s set often look lost on the expansive stage. A more intimate theatre also might have helped the actors tone down their excesses. The other technical elements work well enough, however, especially the stylish second skins into which Lara de Bruijn’s costumes squeeze Ms. Loprest and Ms. Sikor.

Movies about body swapping are legion, among them being FREAKY FRIDAY, THE CHANGE-UP, 18 AGAIN, DATING THE ENEMY, and IT’S A BOY GIRL THING, some of them involving gender switching. So the idea is really old hat and, if you’re going to write a play in this vein it has to be less broadly written and acted, and more consistently humorous and emotionally honest than this one before it can get under your skin.