|

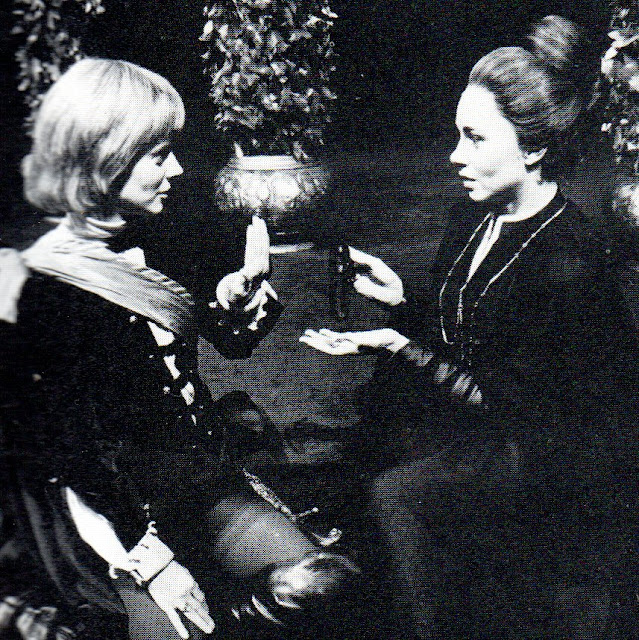

| Leon Russom, Sam Waterston, Gwen Arner, Richard Jordan, Joe Ponazecki, Michael Kane, Ed Flanders, Barton Heyman, Nancy Malone. (Photos: Van Williams.) |

THE TRIAL OF THE

CATONSVILLE NINE [Drama/Crime/Law/Politics/Religion/Vietnam/War] A: Daniel

Berrigan, S.J.; AD: Saul Levitt; D: Gordon Davidson; S: Peter Wexler; C: Albert

Wolsky; L: Tharon Musser; P: Phoenix Theatre and Leland Hayward i/c/w Good

Shepherd Faith Church; T: Good Shepherd Faith Church (OB); 2/7/71-5/30/71 (130);

Lyceum Theatre; 6/2/71-6/26/71 (29) (total: 159)

Note: The present entry includes not only information on the

1971 New York production of The Trial of

the Catonsville Nine, but an extract about the play’s place in the political

theatre of the 1970s from my book Ten

Seasons: New York Theatre in the Seventies (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press,

1986). (Some material in the following overview appears there as well.) For my review in The Broadway Blog of the play’s excellent 2019 revival

at the Abrons Arts Center, please click

on this link.

This controversial

import from Los Angeles’s Mark Taper Forum Theatre was one of the few

significantly political dramas of the 70s. Its initial New York staging was in

an Upper West Side Church redesigned to look like a courtroom. After several

months, it moved to Broadway, but lasted there less than a month.

|

| Michael Kane. |

The Trial of the Catonsville Nine is a semi-documentary play done

in Theatre of Fact style. Its dialogue is edited from the actual transcripts of

the trial at which the radical Jesuit priests, Daniel and Phillip Berrigan, and

their cohorts (seven men and two women), were found guilty of the May 1968

crime of burning 379 draft records at Catonsville, Maryland. The sibling

priests were sentenced to from two to three and a half years apiece in the

Federal penitentiary (they were in prison during the run.) When on trial they

attempt to raise the issue of their moral duty in the face of governmental and

legal restrictions, much as Antigone seeks to do in Sophocles’ Greek tragedy.

Along the way, the contemporary Catholic Church finds itself the target of

political thrusts as well.

The play was

considered artistically clumsy in structure and technique—“like a roughly

edited movie,” griped Jack Kroll, or “a play in name only,” in T.E. Kalem’s

view—but most agreed that the subject matter was so potent it made the play’s

deficiencies seem unimportant. The straightforward directorial style and the

effective performances helped make this plea for civil disobedience in the face

of American involvement in the Vietnam War what Martin Gottfried dubbed “a

powerful and inspiring” event.

“Like so many

courtroom dramas, it makes a positively riveting play,” wrote Clive Barnes. “Everything

sounded as if it were being said for the very first time, with the words

plucked out of the conscience of the speakers.” Those speakers were played by a

large--and, in many cases, distinguished--company including Ed Flanders (replaced on Broadway by Colgate Salsbury),

Barton Heyman, Sam Waterston, Gwen Arner (replaced by Jacqueline Coslow), Joe

Ponazecki, Richard Jordan (replaced by Michael Moriarty), Nancy Malone

(replaced by Ronnie Claire Edwards), David Spielberg (replaced by Josef

Sommer), William Schallert (replaced by Mason Adams), Mary Jackson (replaced by

Helen Stenborg), and Davis Roberts.

The play won an OBIE

for Distinguished Production, Schallert received one for Distinguished Performance,

and Gordon Davidson’s direction earned him both an OBIE and a Tony nomination.

“Political

Theatre in New York during the Seventies and The Trial of the

Catonsville Nine”

Because politics is so important in our lives and is so

infrequently a source of satisfaction to the average man, it is customary in

free societies to laugh at those officials and policies with which we disagree.

Once more, recall the Greeks. Nevertheless, political satire was not especially

noticeable on New York’s stages in the seventies, despite many issues that

cried out for laugh-provoking criticism and comment. Various reasons for this

have been advanced: the disturbing polarization of the nation in the wake of

Vietnam; the possibility that the radical movements of the sixties and early

seventies made political comedy redundant; the painfulness of the issues

involved; a growing feeling of apathy and helplessness, and so on. Whatever the

cause, political satire was not a fruitful mode for most of the decade.

The single most potent image for satirists was that of former

President Richard M. Nixon, who resigned from office in 1973. Of the seven or

eight works that might be termed political satires, four were aimed at him,

although the protagonist’s name was usually disguised. These were Gore

Vidal’s An Evening with Richard Nixon and . . . , the

musical The Selling of the President, Peter Ustinov’s Who’s

Who in Hell, and Pop, a musical farce using King

Lear as its premise.

Other political satires were Rubbers and Dirty

Linen, the first being a deflation of the New York State Assembly, the

second of Britain’s Parliament. Political revues included Eric Bentley’s The

Red, White and Black and What’s a Nice Country Like You Doing

in a State Like This?

Political concerns were present in many plays, but few were

directly addressed to the immediate interests of the American people. Most were

about foreign situations; the subject matter was usually of universal rather

than topical significance. Of the few plays that did look at American issues,

two dealt with the era of McCarthyism. One was Bentley’s docudrama, Are

You Now or Have You Ever Been? Based on the hearings in the forties

and fifties by a subcommittee of the House Un-American

Activities Committee (HUAC) inquiring into the political beliefs of major show

business figures. An interesting feature of the piece was the use of a series

of star actresses to read a famous letter written by Lillian Hellman to the

members of the subcommittee. HUAC was also treated in Gerhard Borris’s After

the Rise with its obvious debt to Arthur Miller’s After the

Fall.

Probably the most controversial of the topical political plays

was The Trial of the Catonsville Nine, a docudrama by Father Daniel Berrigan, S.J.,

one of the participants in the action. (Saul Levitt adapted the piece for the

stage.) It is about the trial of Jesuit priests Daniel and Philip Berrigan and

a group of seven other Catholic activists, two of them women, for having used

napalm to destroy 378 draft files at Catonsville, Maryland, in 1968.

It opened at the Good Shepherd Faith Church, adjacent to

Lincoln Center, where it ran from February 7, 1971, to May 30, 1971, for 170

performances. It then moved for another 29 showings to Broadway’s Lyceum

Theatre, from June 2 to June 26. Gordon Davidson directed. Its Off-Broadway

cast of thirteen, each playing a single role, included such familiar actors as

Ed Flanders, James Woods, Sam Waterston, Richard Jordan, and William Schallert,

with well-known names like Biff McGuire, Michael Moriarty, Josef Sommer, and

Mason Adams joining the Broadway cast as replacements.

The semi-documentary play, staged in a simulacrum of a

courthouse setting and performed in Theatre of Fact style, was edited from the

actual trial transcripts. It was viewed as a plea for the necessity of

civil disobedience as an act of Christian faith. Many legal and social issues

were raised by its attack on contemporary American values and governmental

policies, while it also managed to jab sharply at the Catholic Church. It was

the author’s contention that drama’s purpose is to have a moral impact in the

light of world problems. He condemned theatre that exists only to pass the time

and make money.

During the period when the play was in production, all the

defendants were in jail, sentenced to two to three and a half years. Following

his sentencing, Daniel Berrigan became a fugitive from the law. He was on the

verge of being arrested at Cornell University when he enlisted the aid of the

Bread and Puppet Theatre, who were appearing there. Hiding himself in the

framework of one of their huge puppets, he managed to escape in a van but was

eventually captured and sent to federal prison.

The play was considered artistically clumsy in structure and

technique— “like a roughly edited movie,” rapped Jack Kroll; “a play in name

only,” chimed in T.E. Kalem—but most critics agreed that the subject matter was

so potent it made the play’s deficiencies seem unimportant. The straightforward

directorial style and the effective performances helped make this plea for

civil disobedience in the face of American involvement in Vietnam a “powerful

and inspiring” (Martin Gottfried) event. “Like so many courtroom dramas, it

makes a positively riveting play,” wrote Clive Barnes. “Everything sounded as

if it were being said for the very first time, with the words plucked out of

the conscience of the speakers.”

Plays about political problems pertinent to blacks and women

have been discussed in earlier sections [of this book]. We have seen that

politics was not a major enticement for playwrights dealing with these groups.

Other political topics touched on by American playwrights were the problems of

labor leaders, campaigning for office, the foibles and achievements of past

residents of the White House, political skullduggery in a governor’s office,

upper-class Cuban attitudes toward Castro, and Japanese-American relations in the

nineteenth century.

Many of the decade’s

foreign political plays have been previously described in the book. They

include plays about South African racism, a plot to kill Congolese leader

Patrice Lumumba, colonialism in Africa, the Irish troubles, fascism, terrorism,

and East European dissidents.

Readers

of this blog who may be interested in my Theatre's Leiter Side review

collections (one with a memoir), covering almost every show of 2012-2014, will

find it at Amazon.com by clicking

here.