"It's a Gamble"

The 1992 movie, HONEYMOON IN VEGAS, written and directed by Andrew Bergman, is a high-octane comedy that, while unquestionably imperfect, remains great fun, much of that because of its charismatic stars. James Caan may overdo his Sonny Corleone shtick as the slickly dangerous gangster, Tommy Korman, but he’s never less than magnetic. Nicholas Cage as Jack Singer and Sarah Jessica Parker as Betsy Nolan, the young Brooklyn couple who fall into Tommy’s clutches at a Las Vegas Casino, are in their youthful prime (she was 27 and he 28), and bring honesty and conviction to their farcical experiences to make them both convincing and hilarious. The famous climactic scene, in which Jack, having inadvertently gotten onto a skydiving plane with “The Flying Elvises,” remains a comic masterpiece. It’s such a memorable conception, you know in advance the new Broadway musical version of the film will be working hard to find a suitably theatrical way to replicate it.

The film’s vivid cinematography and bright locales in Brooklyn, Las Vegas, and Hawaii, and its fast-paced, narrowly focused—if totally implausible—plot, position it perfectly for musicalization. The soundtrack, in fact, has so many Elvis songs, it’s already in musical territory. As an overture, so to speak, to the Broadway show (which began in 2013 at New Jersey’s Paper Mill Playhouse), I’d like to describe the movie’s plot, which follows the same arc as the show but differs from it in some significant ways.

Jack, a hapless Brooklyn private investigator without a pot to piss in, has been dating his pretty girlfriend, Betsy, a schoolteacher, for years, while managing to avoid marrying her. It’s not because he doesn’t want to, but because his eccentric mother (Anne Bancroft), on her deathbed, made him promise never to wed. When the frustrated Betsy finally pressures him to tie the knot, Jack succumbs and the pair fly off for nuptials in Las Vegas.

Once there, though, the powerful gambler Tommy, an attractive middle-aged guy, spots the beautiful Betsy, who so closely resembles his late wife, Donna, a sun worshiper who died of skin cancer, that he determines to get her from Jack by suckering him into a poker game, where he’ll lose so much dough he’ll be forced to let Tommy have Betsy for the weekend. The plan succeeds after Jack, holding a straight flush to the queen, loses what seems a sure thing to Tommy’s straight flush to the king.

Owing Tommy the impossible-to-repay sum of $65,000, Jack has no choice but to let Tommy—who promises no hanky panky—enjoy Betsy’s company for the weekend. But Tommy can’t be trusted, and he intends to spend his weekend with the schoolteacher, not in Las Vegas, but at his gorgeous seaside home in Kauai, Hawaii. Betsy reluctantly agrees to go, but Jack, belatedly regretting the arrangement, follows after them.

While Tommy uses his considerable wealth and charm to win Betsy’s affections (including his introducing Betsy to his son and daughter-in-law), Jack is sidetracked in Kauai when trying to reach his girlfriend by Mahi Mahi, a wily old cab driver (Pat Morita), paid off by Tommy to keep Jack from finding him. Meanwhile, Tommy lies to Betsy, who’s beginning to feel bad about the situation, that Jack sold her for the weekend to escape a debt, not of $65,000 but of only $3,000. The furious Betsy now agrees to marry Tommy. The pair depart for Vegas, and Jack, aided by his comical right-hand man, Johnny Sandwich (Johnny Williams), makes sure Jack will be unable to book a flight to follow them.

Jack overcomes many obstacles to get to Vegas in time to prevent the marriage; ultimately, in a last-ditch effort, after various re-routings, he boards a plane in San Jose, California, loaded with Elvis impersonators on their way to the very hotel (Bally's in the film, the fictional Milano in the show) where Tommy and Betsy will be and onto whose grounds they plan to make a mass aerial entrance. Jack has no alternative but to dress like an Elvis and make the jump himself. Betsy is already fed up with Tommy, who, when she expresses her reluctance, not only offers her $1 million to marry him but reveals a seriously menacing attitude when she refuses. Jack’s successful landing brings Betsy back to Jack’s arms and Tommy has to admit defeat.

Even this outline, of course, omits important details, but when a movie is transformed into a musical, a hell of lot more gets thrown out in the condensation process. Musicals require songs and dances, and when they’re underway, plot developments have to wait in the wings. Since Mr. Bergman himself wrote the book for the musical, which has music and lyrics by Jason Robert Brown, we would hope that he knows best about what to cut, what to add, and what to alter in his own material.

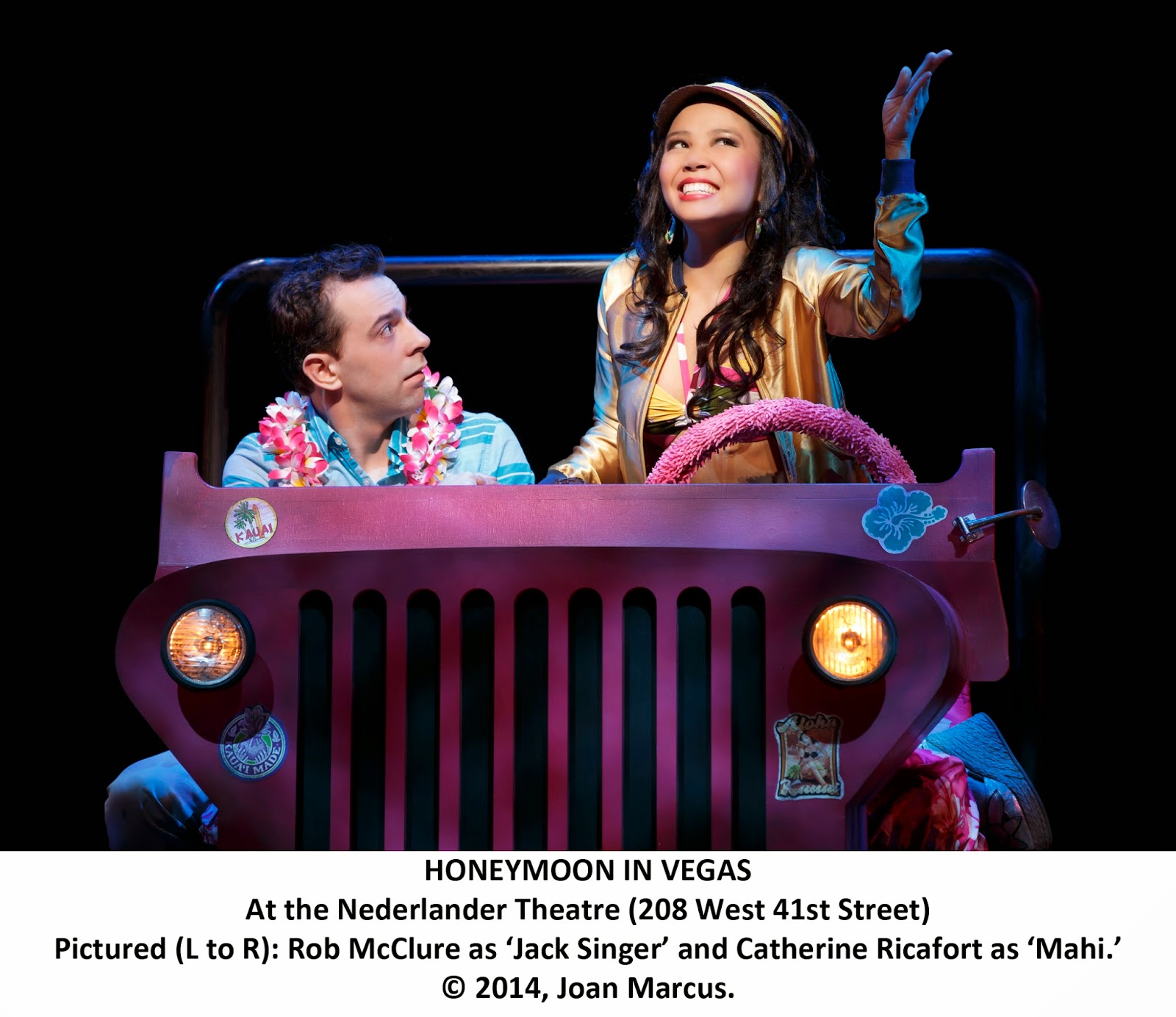

Those fond of the film will be saddened to see that we get no idea of what Jack does for a living; that his Brooklyn dentist buddy (John Capodice) has been cut; that Mahi Mahi, now simply Mahi (Catherine Ricafort), has been transformed into a cute Hawaiian hooker who tries to impede Jack’s quest by offering him “Friky Friky,” the natives’ version of nookie-nookie; that one of the movie’s funniest bits, in which Peter Boyle as a Hawaiian chieftain turns out to be a devotee of Broadway musicals who bursts into songs from SOUTH PACIFIC, has been removed; that Tommy’s actual son and daughter-in-law turn out in the show to be actors hired to fool Betsy; that there’s no physical struggle between Jack and Tommy on the grounds of Tommy’s estate, as Jack tries in vain to shout to the un-hearing Betsy; that Jack catches the Elvis plane, not in San Jose, but in Kauai itself; that Tommy’s threat of violence toward Betsy at the end is dropped so that Tommy remains as likable as possible; and that Jack’s mother, who appears in the movie only in her brief deathbed scene, has become a tiresomely farcical, supernatural—rather than psychological—leitmotif, popping up in unexpected places (like Tiffany's) to sing arias reminding Jack of a curse she’s placed on him. A silly second act scene in which she appears as a Polynesian statue seriously drags the show down, even though the actress, Nancy Opel, has serious comedic and vocal chops.

I’d be curious to know why Jack’s $65,000 debt has been changed to $58,000, and why Tommy’s fib about it being only $3,000 is now $800. Of course, by making the latter sum smaller, Jack’s arrangement with Tommy becomes even more outrageous, but I think the audience would have emitted the same audible “ahhh!” of surprised disgust had the original amount been kept. Still, while relatively annoying, most of these (and other less egregious alterations) don’t seriously threaten the overall entertainment value of the show, which, by the way, pictures the Las Vegas of the movie's era, not the one that exists today. Maybe that's why there isn't a cellphone in sight; had there been, Jack's pursuit of Betsy would have been over much sooner.

Mr. Brown’s deft lyrics are often very amusing, and much of his music—played by a great onstage band led by Tom Murray—brings Rat Pack-era jazzy razzmatazz back to life. Since the Vegas depicted here is a retro reconstruction, we hear a Tony Orlando-style entertainer, Buddy Rocky (a terrific David Josefsberg), singing “When You Say Vegas” with lounge lizard panache. The Hawaiian locale allows for island melodies like “Hawaii/Waiting for You.” When Tommy swindles Jack into giving him Betsy for the weekend, the pair join in the delightful “Come to an Agreement.”

Set designer Anna Louzos creates exuberantly vivid sets that, combining moving units with admirable projections (sometimes animated, like that of a plane landing at an airport), allows the cinematic action to shift instantaneously; she also includes a downstage elevator trap for clever appearances of people and scenic pieces. Brian Hemesmeth’s many stunning costumes make a bold impact, and the showgirls (especially the ultra-long-legged Leslie Donna Flesner and Erica Sweany) wearing his sequined creations in the Las Vegas scenes are among the most eye-poppingly pulchritudinous on the Great White Way. Choreographer Denis Jones provides an assortment of spirited dance numbers, and director Gary Griffin pulls the whole thing together with the necessary energy and imagination; for my money, though, too many bits depend on farcical exaggeration.

Tony Danza’s Tommy, played with silken subtlety, is the most believable of the three leads. Mr. Danza, a trim 63, bears himself with the athletic grace one expects of a former boxer. His Brooklyn background gives him the kind of street smarts to carry off the role of a dangerous Vegas smoothie without having to overdo it. He’s no Sinatra but he sings pleasantly enough, and his second act tap dance is a highlight.

There’s not much to complain about regarding Brynn O’Malley’s Betsy; she’s a terrific singer and an appealing actress, but she’s simply too beautiful and glamorously accoutered and made up (especially that impossibly gorgeous ash-blond hair), making her an unlikely Brooklyn teacher but a prime candidate for Barbie Doll look-alike of the year. Mr. McClure, lithe and amiable, isn't vaguely authentic as a Jewish boy from Brooklyn; his singing voice has a nasally metallic quality, and, while he does all the right things, he never goes beyond skin deep in bringing Jack to life.

Nederlander Theatre

208 W. 41 Street, NYC

Open run