“There’ll Be a Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight”

(Note: parts of what follows are loosely adapted from my May

2015 Broadway Blog review of this show’s Off-Broadway

original.)

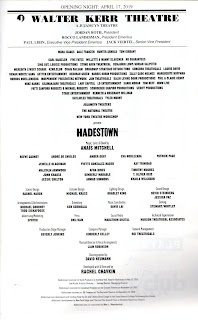

Be careful if you’re walking past the Walter Kerr Theatre

on W. 48th Street during a performance of Hadestown.

You may feel a blast of infernal musical theatre heat coming from inside, where

this red-hot show has finally moved following its 2015 Off-Broadway debut at

the New York Theatre Workshop, and productions in Edmonton, Canada, and London’s Royal National Theatre.

I found its script dramatically “flavorless” in its

earlier manifestation but my taste buds have matured since then. While not its

strongest feature, Hadestown’s book

now seems a fine wine accompaniment to a spellbindingly scrumptious theatrical feast.

Hadestown is a mostly

sung-through musical conflating the Greek myth of Hades and Persephone with that

of Orpheus and Eurydice, and swirling about themes of power of music, love, and

trust. It originated as a compilation of New Orleans-style jazz, folk, and

blues tunes by folk singer-songwriter Anaïs Mitchell.

In 2010, after being performed at various Vermont venues it

became an hour-long, concept album. The album was then developed by

Mitchell and the exciting young director Rachel Chavkin (Natasha, Pierre & the Great Comet of

1812) into Hadestown,

which runs around two and a half hours. Each song is distinctive, and several

are true show-stoppers.The 2015 production was shorter but felt longer; the

audience at the Broadway version behaved like it wasn’t long enough.

For the NYTW staging, set designer Rachel Hauck gutted the

space to build a wooden arena with the orchestra slotted in at one point and

the audience seated on uncomfortable old wooden chairs (unmoored cushions

supplied). A huge, leafless tree that no one ever climbed towered in one corner.

Aided by lots of smoke, Bradley King’s flamboyant

lighting, sometimes enhanced by small lanterns, sculpted the action in rock

concert style, while actors in close proximity to the spectators created a

mildly immersive ambience.

For Broadway, the auditorium remains unchanged and Hauck’s

new design places the show entirely within the proscenium, with an upstage curved wall suggesting

New Orleans French Quarters architecture. In the middle rises a winding

staircase, with ornate wrought iron railings, leading to a balcony fronting

large double doors. Behind them is the dwelling of Hades, dictatorial ruler of Hadestown.

The seven-member orchestra is dispersed along the wall at left, right, and center.

At center are three turntables, one inside the other, capable of running counter to one another. The central disk also serves as an elevator

trap. Chavkin’s staging, and David Neumann’s choreography, make abundant use of

these mechanical aids with remarkably effective results, creating moving arrays

of actors moving in different directions, left, right, around, up, and down.

And King’s lighting, again making much use of smoke,

outdoes itself in evoking mood-setting effects, including a sequence when about

a half-dozen hanging metal lamps are choreographically incorporated into the

action.

Of the original leads, only Patrick Page and Amber Gray

return. Orpheus, first performed by Damon Daunno, presently playing Curly in

the new revival of Oklahoma!, is taken

by Reeve Carney (the original Peter Parker/Spider-Man in Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark), a high tenor ranging into falsetto.

Euridice, taken Off-Broadway by the superb Nabiyeh Be, is now the responsibility

of the equally talented Eva Noblezada (Miss

Saigon).

The chorus-like Fates, mentioned below, are also new:

Jewelle Blackman, Yvette Gonzalez-Nacer, and Kay Trinidad, taking the roles

created by Lulu Fall, Shaina Taub, and Jessie Shelton. And Hermes, who serves

as narrator, is Broadway veteran André de Shields instead of Chris Sullivan.

The show (whose plot summary can be found here) is principally concerned with the tragic, mythical

romance of Orpheus, the gifted lyre musician (read: guitar), who descends to

Hades to bring his lost-girl sweetheart, Eurydice, back to the world of the

living. Only after hearing the finished version of the song Orpheus has been

constantly working on (intended to bring the contentious world together) does Hades relent. He insists, however, that, if Orpheus looks back to see whether Eurydice is following

him, she’ll have to stay in Hadestown forever.

In 2015, I was disappointed that a

show inspired by a tale dramatized in countless films, plays, and operas (from

classical to rock) had squeezed so little drama from it, despite the uniformly

appealing songs and the infusion of a capitalistic exploitation theme. Because

the songs are mostly preoccupied with atmospherics and emotional responses,

their lyrics only indirectly offer exposition, reveal character, or move the

plot along.

These factors seem secondary now; enough is revealed by

Hermes’ narration to serve the story and characters. The latter, after all, are

intended more as iconic figures than flesh and blood human beings, although we

can’t help but become affected by them as superbly embodied by these warmly

human actors.

The basic myth remains intact although Eurydice, a

runaway, goes to Hadestown (by train, it should be noted), not because she’s

dead but as a personal choice, seeking to escape the hard times up on top

where, the lyrics say, “the chips are down”; her road to Hell is paved with

good intentions.

Hadestown’s existence is intentionally ambiguous; the citizenry

is composed of slave-like laborers in leather workers’ gear, moving in rhythmically

robotic fashion, like figures in an old Soviet Expressionist movie. Everyone seems

dead and everything’s symbolic, not to be taken literally, but freedom is

clearly a dream the workers’ share.

Hades’ wife, Persephone (Amber Gray, as before, sassily

sensational and a sure bet for an award nomination), represents the seasons;

she’s something of a snow bird, living half the year above ground, half under.

The suave, black and white, pinstripe-suited, cowboy-booted,

shades-wearing, white-haired Hades, who wants to protect his people by keeping

the enemy, poverty, away, sings about it in a song, “Why We Build the Wall.” One

of his arms even has a brick-wall pattern on it. The song asks “Why do we build the wall?” to be answered by lines like, “Because we have got

what they have not,” but, ironically, was written well before Donald Trump’s build-the-wall fetish. (Patrick

Page’s indelible performance, btw, definitely deserves a nomination.)

The Fates, a trio of gorgeous women garbed in gray and

silver turbans and dresses suggesting Roaring 20s Creole-style flappers, comment

on everything in perfect harmony, sometimes playing instruments. The main

narrative functions fall to the slick-as-ice, slim-as-a-whip Hermes, decked out in a jazzy,

vested, silver suit, with what resemble flaring feathers at his cuffs.

Some of Michael Krass’s masterful costumes are reminiscent

of their Off-Broadway predecessors, others are totally reimagined. Orpheus, for

example, originally dressed in James Dean-like jeans, t-shirt, and red

windbreaker, now wears old sweatpants, a white t-shirt, and a red bandanna. Persephone,

though, still brings Billie Holiday to mind in her pale-green, floral-print

dress and occasionally-worn hair ornament.

Hadestown, with its extensive use of old-fashioned-looking mics,

and even a section where Persephone introduces each orchestra member for

applause, is not that far from being a brilliantly-staged concert. But it now

seems far more dramatically fleshed out than I remember, and many will be emotionally moved by

its tragic story. Judging by the unanimous standing ovation that greeted its

conclusion (wait for Persephone’s uplifting curtain-call song, "I Raise My Cup"), there are going to

be hot times in old Hadestown for

many nights to come.

Walter Kerr Theatre

219 W. 48th St., NYC

Open run

OTHER VIEWPOINTS: