"Awake and Spring"

|

| Stars range from 5-1. |

SPRING AWAKENING, the 2006 Broadway musical adaptation of Frank Wedekind’s revolutionary 1891 German play FRÜHLINGS ERWACHEN: EINER KINDERTRAGÖDIE (usually rendered SPRING’S AWAKENING), which won eight Tonys, has returned in a unique and potent new staging. This production, brilliantly directed by Michael Arden and choreographed by Spence Liff, is a creation of Los Angeles’s Deaf West Theatre and was originally seen at the Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts, Beverly Hills. It’s especially memorable because nearly half of its 22-member cast is made up of deaf actors.

The deaf actors sign while speaking actors say and sing their lines, sometimes while standing right next to their doppelgängers and sometimes while hidden in the shadows. Meanwhile, other roles are played by hearing actors who either already knew how or have been trained to express themselves in American Sign Language. A number of sequences are performed with the words projected on the various surfaces, while other scenes are intensely silent, depending solely on ASL, facial expressions, and projections. These can be especially powerful because they thrust the audience into the soundless universe of the unhearing actors, a contrast made all the sharper by being sandwiched between numbers from composer Duncan Sheik’s often crashing rock score.

Clever as all this is, however, it may take you some time to become accustomed to what, at first, can be distracting as your focus switches between the actor playing a role and their voice double, who may be at the other side of the stage or on a different level. Depending on the circumstances, the voice actors, who are often self-effacing, and who may also be performing on a musical instrument, may or may not be dressed like those they’re voicing. Eventually, though, you pay attention to the character rather than their vocal source. In a very few instances, deaf actors voice some words on their own.

Further, some actors portray several roles, both those they’ve been cast in and others for whom they provide the voices. Patrick Page, for example, who owns what may be Broadway’s most resonant male voice, can be heard as Herr Sonnenstich, Herr Rilow, Father Kaulbach, Doctor Von Brausepulver, and Herr Gabor. Camryn Manheim, the show's other well-known hearing actor, is similarly busy. The deaf actors of comparable esteem, Marlee Matlin and Russell Harvard, also cover multiple roles: she portrays Frau Bergmann, Fraülein Knuppeldick, and Fraülein Großebüstenhalter, while he handles Headmaster Knockenbruch, Herr Stiefel, and Father Kaulbach.

Wedekind’s tale of sexual repression among students at non-coed high schools in a provincial German town still has relevance, even in our supposedly sexually liberated world. The show—powerfully lit by Ben Stanton and performed in Dane Laffrey’s unit set of towering gray concrete walls, embedded with ladders, staircases, catwalks, and arched alcoves for the musicians—tells of the tragic consequences of such sexual repression, as enacted through several students’ experiences, which encompass a girl’s pregnancy and botched abortion; a boy’s suicide; masturbatory fantasies; paternal rape; homosexual stirrings; sadomasochism; and reform school brutality. Parents are prudish and cruel, teachers excessively strict, the church inhumane, and reform schools dangerous.

If you’re wondering how such material could exist in a play written in Wilhelmine Germany you’ll be relieved to know it took 15 years for the original to be produced and then only after considerable modifications. Even finding a publisher was difficult, and Wedekind had to pay out of his own pocket for its printing.

Since the score is rock-oriented, the production meshes contemporary teenage behavior (including profanity) with the 19th-century environment, nicely captured in Mr. Laffrey’s costumes. Mr. Sheik’s music emphasizes beat over melody, offering insufficient variety, as well as little lyricism in the form of conventional ballads. Mr. Sater’s elliptical and repetitive lyrics have punch but can be innocuous and unsubtle (one song is called “My Junk Is You”). Mr. Arden and Mr. Liff keep the actors moving in interesting formations, in one scene having a bunch of teens melded together to represent a tree, in another using tiny lights on gloved fingers for memorable effect. Fluid sign language, combined as it is with vivid facial expressions, adds to the visual impact.

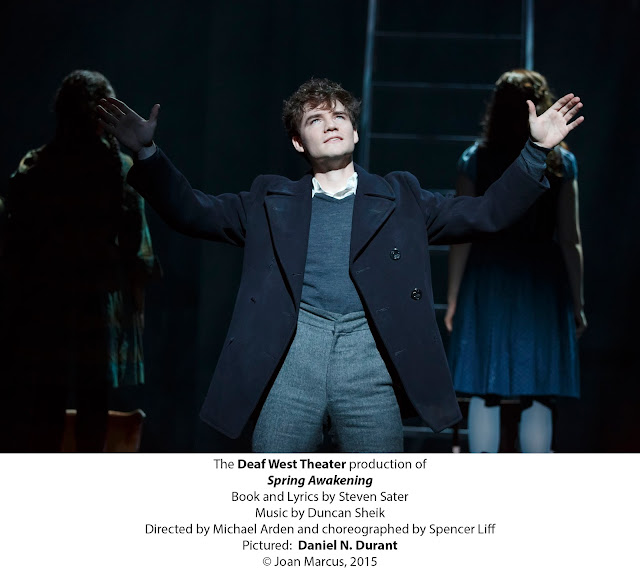

Wedekind’s play, whose episodic style is acknowledged as a precursor of expressionism, is fully realized in the dynamic staging, but there’s also a cool grayness to the enterprise that, despite the tragic events depicted, creates a sense of distance, making it easier to appreciate intellectually than to experience emotionally. This doesn’t detract from the superlative performances, with special kudos to the hearing but ASL-fluent Mr. McKenzie’s Melchior, an impassioned freethinker; the deaf Mr. Durant’s confused Moritz (splendidly voiced by guitarist Alex Boniello), whose raging hormones interfere with his studies; the deaf Ms. Frank’s innocent Wendla (lovingly doubled by guitarist/pianist Katie Boeck), who accepts her mother’s ridiculous explanation of procreation, and, hearing from a friend whose father beats her, asks the same from Melchior; the hearing Andy Mientus’s Hanschen, leaning toward same-sex love; the hearing Krysta Rodriguez’s Ilse, a decadent model; the hearing but wheelchair-bound Ali Stroker’s Anna, a schoolgirl; and the multiple-role versatility of Mr. Page, Mr. Harvard, Ms. Manheim, and Ms. Matlin.

Autumn may be in the air outside, but at the Brooks Atkinson, spring is definitely awakening.

OTHER VIEWPOINTS:

Brooks Atkinson Theatre

256 West Forty-Seventh Street, NYC

Through January 24, 2016