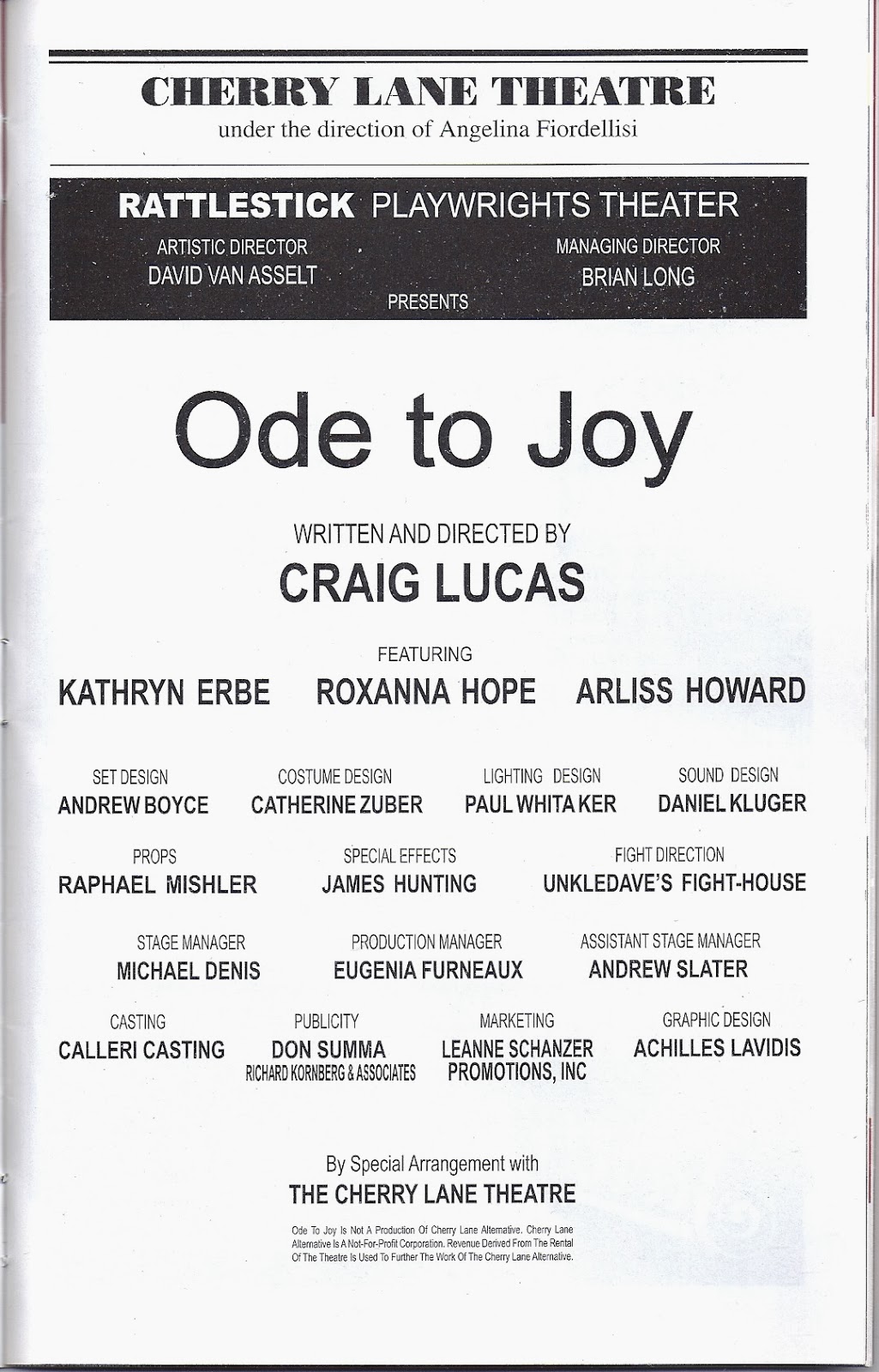

Despite

its optimistic title, getting to the final scene of Craig Lucas’s new play, ODE

TO JOY, when the suffering characters finally discover the presence of that

uplifting feeling, is a rather joyless theatrical trip. Now playing at the

Cherry Lane Theatre in a slow-moving staging provided by the playwright

himself, the play has many dramatic elements, but few of them mesh artfully or

convincingly, and the result is more an ode to depression and substance abuse

than anything approaching joy.

Kathryn Erbe, Roxanne Hope. Photo: Sandra Coudart

The play takes place over a period

of fifteen or so years, but it jumps around in time, beginning in 2014,

flashing back to 2007, moving to 1999, returning to 2007, sliding back to the

eve of the Y2K scare, going back to 1999, then on to Y2K again, and finally

tying its loose ends together in the present day. The scenes occur on a set

designed by Andrew Boyce for maximum flexibility to envision a variety of

locales, such as an artist’s studio, a bar, a loft, and a hospital room. The

various design elements, like Catherine Zuber’s costumes, Paul Whitaker’s

lights, and Daniel Kluger, are all serviceable but not especially noteworthy,

and the same might be said of the performances by the otherwise highly

competent three-actor company.

Mr.

Lucas’s themes concern drug and alcohol abuse (which he admits to having struggled with himself), the struggle of an artist to

succeed commercially while refusing to abandon her noncommercial principles,

and the ways we deal with pain and illness, both physical and moral, including

how the artist transforms his or her anguish into beauty. The three characters,

each of them the victim of some awful disease (in addition to the self-inflicted

ones of booze and pill addiction) are Adele (Kathryn Erbe), an attractive

painter whose work presents horrific (one character calls them “scary”) images

that make it difficult to sell; Bill (Arliss Howard), a recently widowed

cardiac surgeon diagnosed with prostate cancer, and also an alcoholic; and

Mala, a pharmaceutical executive who becomes Adele’s lover, but is a victim of

heart disease requiring a transplant. Bill and Adele also are romantically

involved, and even marry and divorce twice, but, just as happens with Mala,

Adele’s issues make it difficult for them to have a permanent relationship; a

third marriage is in the offing at the end, allowing the play to reach what it

hopes is a joyous conclusion, but after two hours of angst amid these talkative

and unappealing characters, it seems highly unlikely that, for all their

blather, any of them will find true bliss.

Arliss Howard, Kathryn Erbe. Photo: Sandra Coudart.

.

The play slogs along, building image

on image, in language that, for all its occasional wallowing in profanity,

sounds pretentious and unnatural. No hint is offered of how time is being

manipulated for dramatic effect, so the sequence of events is cloudy;

occasionally, time jumps occur without warning even within a scene. Now and

then, Adele briefly addresses the audience, as if telling us her story, but not

much is made of this and its presence seems unnecessary.

The actors demonstrate intelligence

and clarity in their choices, especially when speaking Mr. Lucas’s often

self-consciously elusive dialogue, much of it crammed not only with

allusions to torture, but to obscure philosophical (think Kierkegaard ) and

religious (think Jesus Christ) ideas; however, they’re unable to turn these

characters into real people. Ms. Erbe, in particular, with her sweet and girlish

features, is an interesting choice for the character, but she’s ultimately

unconvincing as the self-destructive Adele.

There are a number of crude one-liners

that spark sporadic laughter, as when Adele, dismissing Mala’s criticism of her

paintings, says, “You don’t want a painting. You want an enema.” At one point, when an accident occurs and Bill

and Adele have blood on them, Bill gets turned on. Adele doesn’t find the

moment amorous, but Bill recalls all the women on whom he’s performed cunnilingus

when, let us say, it was their time of month. Coupled with dramatic incidents

such as Adele’s vomiting in Bill’s mouth when making love, it’s hard to avoid

feeling that Mr. Lucas is straining for attention.

ODE

TO JOY seems almost like a Stations of the Cross journey (in 12 steps rather than 14) for its

characters as they trudge toward some form of salvation, especially when

enlightenment is introduced by Bill in what he says have been verified as the

words of Christ: “The kingdom of God is within us,” for example, or “True joy

is acceptance.” Still, for all its upbeat pronouncements before the final

curtain, Mr. Lucas’s new play is anything but an ode to joy.